Yesterday we

looked at the complaint of a “distributist economist” whom we are calling “Tom

Steele,” who claims that workers purchasing a company on credit can never repay

the loan principal because all earnings go to pay the interest. There are a few things wrong with that claim

(like everything), but Steele’s associate, whom we are calling “John Wide,”

made a few statements about ESOPs that are not, strictly speaking,

accurate. We promised to look into those

“alternative facts” today.

|

| "Not 'Kelsonian'? I invented the ESOP!" |

One, Wide asserted that the AT&T

ESOP was not “Kelsonian” because “the shares of a Kelsonian firm are never

traded at all, much less publicly traded.”

Not so. All ESOPs are “Kelsonian” for the simple fact

that Louis O. Kelso invented the ESOP.

There are many ESOPs that own only a portion of the outstanding shares

of the company, with the rest of the shares being publicly or privately traded.

Furthermore,

every ESOP trades in company shares, or it wouldn’t be an ESOP. There are internal trades whenever there is a

diversification option exercised, or the ESOP rebalances or reshuffles shares.

A distribution of

benefits almost always includes both shares and cash, unless the share balances

of terminated participants were repurchased earlier. Most ESOPs repurchase shares immediately so

that all the participant sees is the cash.

Some, however, distribute shares, which the participant can retain or

sell to other parties unless the ESOP has retained the right of first refusal. Wide and Steele appear to have no real

conception of either ESOP theory or practice.

|

| This is a "coupon bond." ESOPs do not issue these or any other bond. |

Two, Wide asserted that “The hopeful

new owner/operators would have to sell enough bonds . . . [and] they’d have to

pay the bond coupons.”

On the contrary,

the usual practice is for an ESOP trust to obtain a loan from a commercial

bank. It signs a note from a lender; it

does not issue bonds for sale to investors.

An investor buys either debt (bonds) or equity (shares). An investor does not issue bonds to purchase shares,

or issue shares to purchase bonds. An

ESOP cannot issue either bonds or shares in any event. It’s not that kind of institution.

Further, “coupon

bonds” are almost never used these days; the term is nearly an

anachronism. We would say “absolutely never,” but it’s possible

someone somewhere is issuing coupon bonds, although one would have to question

his or her business acumen or financial sanity.

This is because “coupon

bonds” are unregistered bearer instruments.

Anyone who presents the coupons to the issuer will receive the interest

payment whether or not that person is the actual owner of the bond. Coupon bonds thereby offer substantial opportunities

for tax evasion and fraud.

|

| The IRS says an ESOP needs an independent valuation, not an "ideal price." |

Three, any ESOP holding

non-publicly traded securities (company shares) is required by law to have a

“proper valuation” at least once a year, and any time there is a transaction

involving a significant proportion of the outstanding shares of the company. According to IRS regulations, this valuation

cannot be decided by the parties to the transaction(s), but must be the result

of an independent appraisal when there is no value set by an established

security market:

4.72.8.1.1 (08-29-2016)

Valuation in Defined Contribution Plans

Valuation in Defined Contribution Plans

In a profit sharing, money purchase or stock bonus plan, the

valuation of assets will determine the value of a participant’s account, and

ultimately, a participant’s distribution.

In an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP), the valuation will

affect both the deduction and distribution. For employer securities that are

not readily tradable on an established securities market, IRC 401(a)(28)(C)

requires all valuations with respect to activities carried on by the plan to be

made by an independent appraiser. See Notice 2011-19, 2011-11 IRB 550 and 26

CFR 1.401(a)(35)-1(f)(5) for the definition of readily tradable on an

established security market.

Four, the chief problem Wide and Steele

have with ESOPs, however, is that they claim the workers can never repay the

acquisition loan principal — not bond

issue — because total cash flow goes to pay the interest on the acquisition

loan (not bond coupons). They also seem to believe that the ESOP must

purchase all outstanding shares of the company at once, or it isn’t really an

ESOP, a demonstrably false assumption.

|

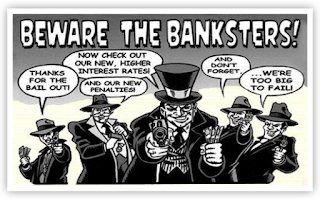

| Steele seems to think all bankers are inherently dishonest. |

And why do Wide

and Steele believe that?

Because many

people who purchase capital use what is called the “discounted cash flow method”

to determine if the price of the company asked by the seller is less than or

equal to the value of the company to the buyer.

In effect, Wide and Steele tacitly assume that the discount rate used by

the prospective buyer is the same as the return to the company on invested

capital (“Return on Investment,” or ROI), and is also the same as the interest

rate on the acquisition loan.

Therefore (Wide

and Steele reason), assuming that the buyer and seller disregard the legal

requirement of an independent appraisal and agree on the value of the company

by the discounted cash flow method, and since the lender will take all profits

as interest, the buyer of the company — an ESOP trust on behalf of the workers —

will never have a cent extra to repay any of the loan principal, but will be

paying interest in perpetuity.

We are now in a

position to examine Wide’s and Steele’s four principal errors, which we will begin

looking at on Monday.

#30#