Guest Blogger: William R.

Mansfield, Founder, Mansfield Institute for Public Policy and Social Change,

Inc.

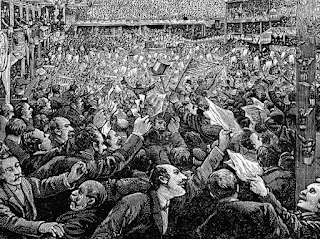

In our postmodern world of rapid change and

complexity, there are no final authorities. Given the greater “wisdom of crowds,”

no single person can direct a complex business. A lone individual can only prod

it to think differently. The postmodern

leader is an activist.

The “Servant Leader”

Indeed, it could be argued that the terms activist and facilitator should replace leader

and manager as more descriptive of

the sort of “servant leadership” today’s world needs. Activists promote change with neither the

authority nor sufficient wisdom to decide matters for a crowd. Facilitators

coordinate the efforts of people to help them achieve goals without actually

controlling them.

Leaders and managers lived in a world of stable

structures with clear boundaries and fixed roles arranged in a neat pecking

order. Similarly, in the Middle Ages, the Earth was the center of the universe

and there was a definite up and down. Now there is no center, no absolute up or

down, or even solid objects. There are

just chaotic collections of particles, seemingly with minds of their own. A world in flux has few stable structures.

|

| Change without plan or principles leads to chaos. |

Organizations driven by constant innovation

have also become unstable and loosely structured. They are fragmenting just as

surely as physical objects that try to move too fast. As a result, our efforts

to understand leadership must shift from the statics of structure to the

dynamics of rapid change. As in the physical world, leadership is no longer a

role in a stable structure but a brief impact that induces an organization to

think differently, even if only momentarily.

The main destabilizing force in business today

is the shifting balance of power. A hierarchy is a power structure. Those at

the top got there by claiming to know best where to take the organization and

how to get there.

If leadership provides direction, it must come

from a crowd where wisdom resides instead of flowing top-down as of old.

Crowd-sourced leadership is a discrete act not an ongoing, stable role. As a

type of action, groups — not just individuals — can show such leadership. It

can also originate from the frontlines or (albeit much less effectively) outside

the organization altogether.

Leaders as Activists

|

| Gary Hamel, author of Leading the Revolution (2002). |

In Leading

the Revolution: How to Thrive in Turbulent Times (2002), Gary Hamel called

on all employees to become activists by advocating new products to top

management, such as did the Sony employee who convinced his bosses to develop

PlayStation. Hamel unfortunately did not

develop the connection between leading and being an activist other than to hint

at it in the title of his book.

Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, and Nelson

Mandela were activists. So are green

campaigners. When activists resort to

violence, as CESJ co-founder Father William J. Ferree, S.M., Ph.D., noted, we

rightly label them terrorists. When they

use constructive approaches to influence us, however, we classify them as

leaders.

Activists, by definition, must campaign for

their causes because they have no authority to make decisions for the groups

they seek to influence. If they succeed

in having a leadership impact, it might be a once-in-a-lifetime event. Activists might have no interest or

qualifications to be leaders in the positional sense.

If leadership is not a role within a group,

then it needn’t be limited to individuals. Thus activist groups like Green

Peace can have a leadership impact on other groups. It is often younger,

creative, rebellious types trying to make their mark who lead as activists.

The Act of Social Justice

|

| Fr. William J. Ferree, S.M. |

To be effective, the true servant leader must sooner

or later (and better sooner rather than later) make the transition from

activist to facilitator. This means,

first of all, belonging to the group.

Simply joining or being a member of a group does not automatically mean

that one belongs to the group, although it is a necessary first step.

As Ferree pointed out, institutional change that

meets the demands of justice cannot be imposed from outside the group. Initiating change from outside the group is

the role of the activist. Actually

carrying out the change can only be done from within the group itself, once a

critical mass has been reached. This is

the principle of subsidiarity; effective agents of change must “subside” or

“subsist” within the group itself.

Subsidiarity in turn requires solidarity, that

is, not just being an “official” member of the group, but accepting and

internalizing the principles that define the group as that group, and no other. Neither

the leader nor any other member of the group can just be in the group. He or she must

truly belong to the group — and the group to him or her.

In other words, the servant leader, like

everyone else in the group, must learn to love the institution as he or she

loves himself. This is “social charity,”

the essential precondition to “social justice.”

|

| Aristotle: Do good, avoid evil. |

That’s because just as individual charity

fulfills and completes individual justice, the justice directed to the individual good, social charity fulfills

and completes social justice, the justice directed to the common good. And the common

good is that vast institutional network within which people become more fully

human by becoming “virtuous,” that is, by building habits of doing good and

avoiding evil.

Thus, in order for people to build individual

habits of doing good (“virtue”), their institutions — their “social habits” —

must embody “structures of justice” that enable people to be virtuous most

effectively. This means that, if the

group’s institutions are not justly structured, people in the group must

organize to transform them from structures of injustice, to structures of

justice.

Personal Empowerment

The question then becomes how individuals within

a group gain the ability to carry out effective social change. It cannot be done by the command of the

leader or wishful thinking on the part of other group members. It can only be done by ensuring that each and

every member of the group is empowered, that is, has power: the ability for

doing.

And this leads to a serious problem in today’s

business environment. “Empowerment” in

most schools of management doesn’t mean having

power as a right, it means being given power as a gift.

|

| "We are, like, so empowered . . . not." |

That’s because the definition of “empowerment”

in many of today’s business textbooks is “Allowing workers to make decisions up

to a predetermined dollar amount.” The

common example is restaurant or hotel workers who are permitted to “comp” upset

guests if the cost falls within a certain range. This helps convince guests that their

concerns are so important that they are taken care of immediately instead of

being referred up the chain of command.

Obviously that sort of thing isn’t true

empowerment. It’s just a company policy

to keep customers happy. If it turns out

it costs too much or doesn’t work, the policy can be changed and the workers

“dis-empowered.”

True empowerment means having power that cannot

be taken away, and in almost all cases that requires ownership of part of the

company — “Power,” as Daniel Webster said, “naturally and necessarily follows

property.”

The real power in a company is vested in the

owners, that is, the shareholders . . . or it should be. There are, frankly, serious problems these

days with the government and large owners denying minority owners their full

rights, including the right of control and the right to receive their fair

share of income — but that’s a discussion for another day.

Thus, if leaders truly want to empower workers

so that everyone can fulfill his or her obligation to care for the common good

of the company, he or she must organize with the workers to make everyone a

co-owner as fast and effectively as possible.

Otherwise, the leader may bear the title of facilitator, but he or she

is nothing but a dictator.

#30#