You’ve probably noticed that the moment you think you’ve heard it all, somebody is bound to show up and prove you wrong. For example, if you ever thought that today’s academics and politicians were crazier than bedbugs and nobody in history, except maybe Caligula and a few other loony toons, could match them.

Hold my beer . . .

Let’s consider the case of one Ignatius Loyola Donnelly. Born in the 1830s, Donnelly was an attorney, politician, and writer . . . and a socialist real-estate speculator and a few other things polite people don’t talk about except in cocktail parties. He started out a Catholic but ended up a spiritualist. (Walter Monfried, “The Astonishingly Inconsistent Ignatius Donnelly,” The Milwaukee Journal, August 19, 1974, 10.) A populist socialist who hated William Jennings Bryan (possibly for the Great Commoner’s overt Christianity), he corresponded with and supported the agrarian socialist Henry George. He has been described as “America’s ‘Prince of Cranks’.” (Walter Monfried, “America’s ‘Prince of Cranks’,” The Milwaukee Journal, May 15, 1953, 8.)

|

| Atlantis |

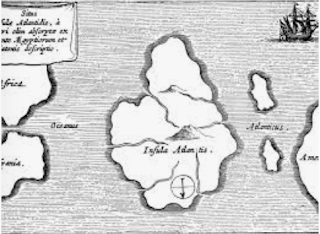

Donnelly is best remembered today for his accounts of the high Neolithic civilization that allegedly existed before Noah’s Flood. Possibly dictated to Donnelly by an Atlantean spirit guide, these were Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882) and Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel (1883). Madame Blavatsky, founder of the most widespread school of theosophy, cited Donnelly’s Atlantis several times in The Secret Doctrine. By the way, the racial theories of the Nazi Third Reich came out of theosophy, if you didn’t know.

|

| Donnelly high hatting the marks |

As a Congressman during the Civil War Donnelly took a $50,000 “legal fee” from the Frémont presidential campaign for unspecified “legal services” to help unseat Abraham Lincoln. We know it was a “legal fee” and not a bribe, because in the 1890s a newspaper called it a bribe and Donnelly sued for $100,000 . . . and won, there being no hard evidence to support the allegation that the “legal fee” was in fact a bribe. The court awarded Donnelly $1, and he had to pay his own court costs.

Donnelly was also the promotor of the town of Nininger — he was thereafter known as “the Sage of Nininger” evidently for his skill in ripping off people and making them feel good about it — which made him a fortune until it went bust. Today it’s characterized as a modern Atlantis, being completely submerged. He also made another fortune in real estate speculation but lost both of them. This was during the period in which he claimed that no individual has the right to own land.

|

| Donnelly sneering at the unenlightened |

Several interesting, if unconventional, theories appear fictionally in Donnelly’s novels. The Jewish menace figured large, as did the Yellow Peril and other nineteenth century bogeymen. These are Caesar’s Column (as Edmund Boisgilbert, 1890), Doctor Huguet: A Novel (1891), and The Golden Bottle, or, The Story of Ephraim Benezet of Kansas (1892).

In the field of literary criticism, Donnelly developed complex formulae to prove his contention that Shakespeare did not write the plays attributed to him. Francis Bacon wrote them to convey Occult spiritualist messages to his disciples in the future. Donnelly’s argument is presented in The Shakespeare Myth (1887), The Great Cryptogram: Francis Bacon’s Cipher in Shakespeare’s Plays (1888), and The Cipher in the Plays, and on the Tombstone (1899). He was laughed off the stage in London when he took his show on the road there.

The English writer G.K. Chesterton wrote Donnelly off as “some American crank” in his book, The Everlasting Man (G.K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man. New York: Image Books, 1955, 206.) One reviewer described the cypher as “a worthless and silly piece of nonsense. . . . the work of a crank or a humbug.” He concluded, “Such men as Mr. Donnelly can thrive only when the ignorant and the curious support them.” (Arthur Mark Cummings, “Letters to Theodore, IX,” Boston Evening Transcript, July 3, 1888, 10.) The judgment rendered in his obituary was that he was “ruled by his imagination more than logic” (“Ignatius Donnelly,” The Toledo Weekly Blade, January 10, 1901, 4.) and that, “though he was a man of great mental powers he was dominated by the erratic and unfounded.”

But wait! There’s more!! The noted social justice advocate and “Father of the Living Wage” Msgr. John Augustine Ryan of the Catholic University of America in his early teens read and was inspired by Henry

|

| Donnelly's biggest fan |

George’s Progress and Poverty . (Rt. Rev. Msgr. John A. Ryan, D.D., L.L.D., Litt.D., Social Doctrine in Action: A Personal History. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1941, 9.) He also became “much interested in the proposals for economic reform advocated by Donnelly, the Farmers’ Alliance (an agrarian reform movement that eventually became the Populist Party), and the Knights of Labor.” (Ryan, Social Doctrine in Action, op. cit., 12.)

Ryan claimed Donnelly “exercised more influence upon my political and economic thinking than any other factor.” Ryan believed Donnelly’s interest in the Occult demonstrated his intellectual scope, while his science fiction and fantasy novels contained innovative concepts that were integrated into his political thought.

And you thought today’s politicians were nuts.

#30#