In the

previous posting on this subject, we looked at how commercial banks really

create money. It turns out that

(contrary to popular belief) commercial banks don’t usually make loans out of

their reserves, but by creating money backed by the value of the financial

instruments they accept.

|

| Keynes: "My myth ath good ath a mile." |

We also discovered that the so-called Keynesian money

multiplier is a myth. Depositing a check

in a commercial bank does not increase the amount of cash in the system. Instead, since a check is a claim on existing

reserves, all that happens is that reserves are moved from one bank to another. The amount of cash in the system stays the

same.

That being said, what then is the use of having reserves?

As we explained in the previous posting, reserves must be

on hand to ensure that if someone presents a check or other obligation drawn on

the commercial bank for payment, the commercial bank will have enough cash on

hand to satisfy the legal claim for cash.

Of course, since banks are presenting claims to other commercial

banks at the same time other commercial banks are presenting claims to them, commercial

banks don’t have to satisfy every claim in cash.

For example, if I owe you $20, and you owe me $25, do I

need $20 to pay you, and you need $25 to pay me, for a total of $45? Of course not. All we need in total is $5 in your pocket to

pay me the difference between what I owe you and you owe me. The $20 I owe you cancels out $20 of the $25

debt you owe me, leaving you owing me the net of $5.

Thus, of the total demand for cash of $45, we only actually

need $5, so why carry around cash we don’t need? After all, we all have better uses for cash

than to carry it around. We only need a “fraction”

of the total cash involved in the transactions — we can have “fractional

reserves.”

|

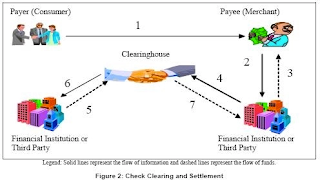

| Clearinghouse operations (simplified). |

Commercial banks operate the same way. Because not all obligations of a commercial bank

will come due at the same time, and because many if not all obligations the commercial

bank owes to others can be offset against what others owe the bank, banks only

need to have a relatively small amount of cash on hand at any one time.

And that could cause problems. For example, there was a “dirty trick” banks

used to play on other banks they wanted to drive out of business back before

there was a regulated clearinghouse system.

Rather than banks presenting obligations directly to other banks, a

clearinghouse acts as a middleman between banks, making sure that all

obligations are met and preventing the dirty trick we’re about to describe.

|

| Dirty tricks common in banking and Hollywood |

Bank A wants to drive Bank B out of business, and Bank A

knows that Bank B only has $100,000 in reserves on hand. Bank A “holds back” the obligations of Bank B

it receives until they total more than $100,000, and presents them all at one

time to Bank B for payment. If Bank B

cannot find more reserves quickly, it goes bankrupt, and gets taken over by

Bank A as the new owner. Bank B had

assets worth far more than the amount of obligations that Bank A suddenly

presented for payment, but they were not in cash, and could not be turned into

cash fast enough to satisfy Bank A . . . especially if Bank A had already gone

around to any other banks in the area and told them not to buy any of Bank B’s

assets for cash.

Clearinghouses were invented in part to stop this sort of

thing. If more obligations came through

the clearinghouse than a member bank could meet at one time, the clearinghouse

could lend the bank additional reserves, or immediately arrange for the bank to

borrow additional reserves, charging a fee for the service — and keeping the

bank in business. Further, if it was

obvious that one bank was playing the dirty trick on another bank, the

clearinghouse could warn the offending bank or even deny access to the

clearinghouse.

|

| Bankers get nervous |

There are other problems with fractional reserve banking

that are not so easily solved. By making

the amount of money a bank can create depend on something other than the creditworthiness

and financial feasibility of the borrower and the actual loan, a monkey wrench

is thrown into the decision-making process.

For example, suppose there is a 10% reserve requirement

and a bank has $100,000 in reserves.

Unfortunately, while the bank can legally create new money in the amount

of $1 million, only $600,000 worth of sound loans are brought to the bank for

financing.

Bank management gets nervous. “We’re losing money by not making another

$400,000 in loans!” They have an

incentive to make bad loans just because they can, in an effort to make more

money.

But what if more good loans are offered to the bank than

the bank is allowed to make? The same

thing happens in reverse. Bank

management gets nervous. “We’re losing

money by not making perfectly good loans!”

They have an incentive to agitate for lower reserve ratios . . . which

is fine until good loans stop coming in, in which case they again have an

incentive to make bad loans.

The problem is that fractional reserve banking is not

supposed to encourage bad loans or discourage good loans. It is supposed to be a way to ensure that

existing obligations of a bank have adequate “coverage.”

|

| An essential tool ... if used properly. |

Frankly, with modern communications and a clearinghouse

system overseen by a central bank, there is no need of reserves for anything

except to satisfy customers who want cash in hand. Today, any and all financial assets of a bank

can be converted into additional reserves in an instant. That being the case, all outstanding

obligations of a bank should be converted into reserves immediately by selling

them to the central bank.

Why?

Because only “qualified paper” (i.e., sound loans)

can be sold (“rediscounted”) to the central bank, thereby increasing the probability

that only good loans will be made. If a

bank’s loan officer knows that a loan must be rediscounted, and cannot be made

unless it is believed to be a good loan, the incentive to make bad loans knowing

they are bad disappears.

Further, if a bank must have 100% reserves, no matter

what, there is no need to try and manipulate a change in reserve requirements

which can cause future problems. Loans

can be judged solely on whether they are good or bad in and of themselves. All good loans can be made, while bad loans

won’t qualify for rediscounting and so won’t be made in the first place.

Of course, all we’ve been discussing up to now is what

money is and what commercial banks and central banks do. There is a lot more to that, but before we go

any further we need to know not only what money is, but what it, too, does —

and that involves looking at something called “Say’s Law of Markets,” which

will do in the next posting on this subject.

#30#