As we saw in our

previous discussion on this subject, the 1912 presidential campaign

was blessed — or cursed — with an abundance of parties and candidates,

including a few nobody remembers. There

was only one previous campaign of national importance in United States history

that even came close to the variety of candidates and positions in the public

eye.

There have been a

large number with many more candidates and positions, of course, but not that

achieved national recognition for so many.

That one was the New York City mayoral campaign of 1886. By coincidence, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. was a

serious contender in both the 1886 New York City campaign and the 1912 national

campaign.

With that as our

segue, then, today we’ll look at the Republican candidate, and the Progressive

Party candidate:

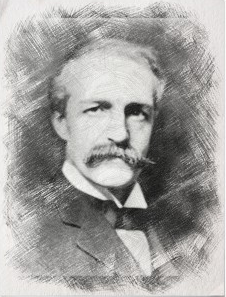

The Candidates: Taft

|

| William Howard Taft |

The candidate for

the Old Guard Republicans was, of course, Taft. Although handpicked by

Roosevelt as his successor to carry the progressive torch, Taft had shown

himself unequal to the task.

Early in his

term, Taft had come under the influence of Senator Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich

(1841-1915), whose primary concern was to maintain power by quashing the

progressive Republican insurgents. Aldrich was the acknowledged leader of the

reactionary Republicans, and hand-in-glove with the Wall Street capitalists who

sought to keep all financial power concentrated in their hands.

It was, however,

the “Ballinger Affair” that triggered the break between Taft and Roosevelt.

This eventually led to the progressive Republicans splitting off, and left Taft

at the mercy of the reactionary elements of the Republican Party.

Briefly, as one

of his first acts as president, Taft replaced Roosevelt’s Secretary of the

Interior, James Rudolph Garfield (1865-1950), son of the murdered James Abram

Garfield (1831-1881), twentieth president of the United States, with Richard

Achilles Ballinger (1858-1922), past mayor of Seattle. Conservationists widely

interpreted this as a break with Roosevelt’s policies.

|

| Gifford Pinchot |

In this they were

justified. Ballinger almost immediately restored more than three million acres

of land set aside for preservation to private use. Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946),

the 1898 appointee of William McKinley (1843-1901) to head the Division of

Forestry who had run the U.S. Forest Service since 1905, believed that

Ballinger’s goal was to end the conservation movement.

Pinchot claimed

that Ballinger was favoring the trusts in water power issues and arranged for a

meeting between Taft and Louis Russell Glavis (1883-1971), head of the

Portland, Oregon, General Land Office. Glavis submitted a report to Taft

alleging that Ballinger had an improper interest in the handling of coalfield

claims in Alaska and had interfered in the investigation of coal claim

purchases in Idaho.

Taft exonerated

Ballinger and fired Glavis for insubordination. Taft’s efforts to placate

Pinchot and convince him that his administration was pro-conservation were

unavailing. Pinchot sent an “open letter” to Senator Jonathan Prentiss Dolliver

(1858-1910) criticizing Taft, praising Glavis, and requesting a Congressional

investigation into Ballinger’s activities.

Taft fired

Pinchot, but investigations were carried out, anyway. Ballinger was cleared

(there remains the possibility that the outcome may have been politically

motivated. . . .), but criticized for subordinating conservationism to private

business interests.

|

| Robert Marion La Follette, Sr. |

The Ballinger

Affair is credited with starting Senator Robert Marion La Follette, Sr.

(1855-1925) on the path that eventually led to La Follette’s reorganization of

the American Party as the Progressive Party, more popularly known as the “Bull

Moose” Party, after a remark by Roosevelt. As a result, Taft was widely perceived

as having abandoned the progressivism that had gotten him elected.

To all intents

and purposes, then, Taft was unelectable — as he was fully aware. Taft had

hated being president, anyway. He remarked years later that his tenure in the

White House was a barely remembered nightmare, reportedly stating, “I don’t remember that I ever

was president.”

Taft’s only

reason to run was to ensure that Roosevelt lost, and he could best do that by

keeping the Old Guard Republicans from joining the progressives. This he could

do without any campaigning at all. In fact, except for his speech of acceptance

for the nomination, Taft refused to do any public speaking. Taft even remarked

that he did not even consider himself a real candidate, as “[t]here are so many

people in the country who don’t like me.”

The Candidates: Roosevelt

|

| Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. |

Despite the

“legend” that has come down to us about how Roosevelt decided to run for

president on a third party ticket in a fit of pique, destroying Taft’s

reelection bid by splitting the Republican Party, the issue was not so simple

or clear-cut as all that. Roosevelt was far from enthusiastic about being

president again. It is not all that certain he particularly enjoyed it the

first time.

Reading the

various biographies of Roosevelt, one is struck by the man’s sense of duty. He

might brag afterwards about something he had done — but you could be sure that

he had done it. Sometimes he seems to have enjoyed having done something more

than doing it.

Still, we do not

recall reading that Roosevelt ever bragged about something he was going to do. Having done something,

however, Roosevelt was not going to hide his light under a bushel, however

irritating that might be to people who preferred to hear less about the

achievements of others, and more about their own.

That is why H.K.

Smith’s recollection of Roosevelt’s decision to run again in 1912 is so

valuable. It is not the speculation of a historian with an ax to grind, or a

politician with an agenda to advance, but an eyewitness account by a man who

knew Roosevelt. As Smith related,

|

| H.K. Smith |

Some time in 1911 I called upon Colonel Roosevelt at the Outlook

office, on leave from Washington. I told him I was going home for a few days.

He pounced down on me instantly: “H.K., don’t you dare go back to Connecticut

and do anything for my nomination for the Presidency in 1912!” Then he said:

“I’ve had eight years of the Presidency. I know all the honor and pleasure of

it and all of its sorrows and dangers. I have nothing more to gain by being

President again and I have a great deal to lose. I am not going to do

it!” — then he went to the window and looked out on Fourth Avenue for some

moments, and turned and added with great emphasis — “unless I get a mandate

from the American people.” I know much now than I did then what was before his

far-seeing eyes as he stood there looking out over the housetops — the fierce

strive ahead, the menacing issues lying within it, the far-reverberating

results that would follow, the sacrifice that would be required of him.

That mandate came. It became desperately clear to all

Progressives early in 1912 that their accomplished advance was in imminent

period of recession. The pressure came down on Colonel Roosevelt, culminating

in the appeal of the seven Governors on February 10, 1912. He accepted the call

of his friends, the challenge of his familiar foes. (Herbert Knox Smith, “The

Great Progressive,” Foreword to Social Justice and Popular Rule, op. cit.,

xiii-xiv.)

The Progressive

Party had its roots in the formation in 1906 of the American Party in Utah by supporters

of Senator Thomas Kearns (1862-1918), a Catholic. Kearns broke from the

Republican Party when he and his followers felt that the Church of Jesus Christ

of Latter Day Saints (“Mormons”) had too much influence in Utah politics.

Purged of its

anti-LDS elements, the remnants of the American Party became the core around

which progressives and moderate populists coalesced to form the Progressive

Party in 1912. They virtually forced the nomination on Roosevelt once La

Follette proved to be non-viable as a candidate.

#30#