In The American

Republic (1866), Orestes Augustus Brownson (1803-1876) framed the Civil War as a struggle between the

agrarian capitalism of the South, and the industrial and

commercial capitalism of the North, which he characterized as “two mutually

antagonistic systems.” The war, the Homestead Act of 1862, Reconstruction, and (later)

the boll weevil shifted the economy from large-scale production of labor-intensive cotton on latifundia-type plantations, to

small-scale production of capital-intensive

wheat and other crops on the new, yeoman-type homestead farms.

|

| Orestes A. Brownson |

This left industrial and commercial capitalism the dominant form, countered only by the small

ownership of land and small business. Lack of access to capital credit based on future savings, however, ensured that

corporate farming and industrial and commercial consolidation would quickly

replace the family farm and small business as the predominant characteristic of

economic life in the United States.

Dependent on wage-system jobs outside the

family for income, family members would no longer be in a position to “contribute to the common support, according to the capacity

of each.” (Quadragesimo Anno,

§ 71)

|

| Peter S. Grosscup |

In the early twentieth century, Judge Peter Stenger Grosscup (1852-1921) of the United States Seventh

Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago, an associate of President Theodore

Roosevelt, Jr. (1858-1919), made

speeches and wrote a series of articles focusing on the problem of declining

small ownership. Focusing on weaknesses in the Sherman

Antitrust Act of 1890, Grosscup recommended a program of expanded capital ownership through reform of corporate law.

|

| Archbishop John Ireland |

Grosscup was also associated with Archbishop John

Ireland (1838-1918), both being strong

progressives. This was before the term

progressive acquired its current negative connotation and

confused definition. At this time

progressivism was, to all intents and purposes, a synonym for common sense

political and religious orthodoxy. This also applied to the Roosevelt form of Americanism, the essence being to apply

old principles in new ways.

Archbishop Ireland was another advocate of expanded capital ownership, and a friend of Roosevelt. Grosscup and Archbishop Ireland,

who may have become acquainted as a result of the archbishop’s approval of Grosscup’s authorizing the use of

federal troops to keep order during the Pullman strike of 1894, both served on

the Committee on Arrangements of the National Conference on Trusts and

Combinations in October 1907.

|

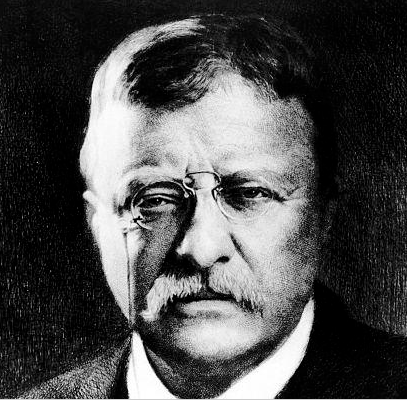

| Theodore Roosevelt |

Unfortunately, Grosscup’s proposals took for granted

the presumed necessity of past savings to finance new capital formation.

This ensured its economic impracticability. Politically, a quarrel with Roosevelt over some legal technicalities in the Standard

Oil Rebate case in 1907/1908 ensured that Grosscup’s proposals to (as Grosscup put it) people-ize the corporation came to

nothing.

Had Roosevelt won the 1912 presidential campaign, Grosscup

might have been able to link his expanded ownership proposals with the new

Federal Reserve system, making it possible for people without existing savings

to purchase capital and securing the wellbeing and independence of the American

family. (There is also the possibility

that Roosevelt, who negotiated the peace between Japan and Russia in 1905,

could have done the same in Europe in 1914 had he been able to bring the prestige

of the presidency to the table, and World War I would either not have happened,

or would not have been a world war.)

Roosevelt didn’t win, and the Federal Reserve was hijacked

by the very people it was intended to keep in check. The money power became even more concentrated

under the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 than under the National Banking Act of

1863, and State control of the economy — and élite control of the State —

became the orthodox political and economic position within a generation.

|

| Fr. Yuhaus presenting Every Worker an Owner to the pope. |

With the Just Third Way and Capital Homesteading, however,

we have the opportunity to turn things around and restore the sovereignty of

the human person and the family as the fundamental unit of society. CESJ has joined with other organizations in

an interfaith effort to present a new vision of an economically just future for

all in the “Five for the Family” campaign with the immediate goal of going to

the World Meeting of Families in September and bringing it to the attention of

the prime movers who will be attending.

Visit the campaign webpage, and share it with your

network. You might also consider making

a small donation to help us meet the expenses of the effort.

#30#