In the previous posting on this subject, we noted how Dickens took Scrooge about as far as he could go with his reformation and completion as a human person — but no further. Scrooge’s character was expanded individually, and his sense of strict justice was completed and fulfilled by charity, but no more.

The social — really, political — aspect of human nature was left untouched. The political environment, which Scrooge as an individual had no power to change, was left unreformed. Advancing technology was still forcing down the economic value of human labor. In addition, methods of finance assumed as a given that only those who had sufficient past savings could acquire the new technologies.

Worst of all, under English common law, any form of control (management, voting, decision making, etc.) or enjoyment of the fruits of ownership (dividends, profit sharing, bonuses etc.) was construed as ownership, whether or not an individual had legal title. This was, in fact, quite proper, given a strict interpretation of the natural law definition of the right to private property and the socially determined rights of private property.

“Property” in fact consists of the rights to and over a thing, not the thing itself. Thus, whoever has the right to control or actually controls the thing, or to receive or actually receives the usufruct (the “fruits of ownership”) is the real owner of the thing, regardless who might be the nominal owner, i.e., who holds “legal title.”

A little confusion enters in when we bring in borrowing and lending, which involves temporary rights to the usufruct of something. When someone rents a thing that is not consumed by its use, he does not become the owner of thing. A renter makes a purchase of the usufruct of a thing on a temporary basis and returns the thing once he is finished with it; title does not pass.

The case is different when a thing is consumed by its use, e.g., food, labor, or money. Food, labor, and money are consumed by their use and cannot be returned once used. The usufruct cannot be separated from the thing itself, and thus food, labor, and money cannot be rented, only purchased; title passes.

|

| "Now THAT'S a humbug!" |

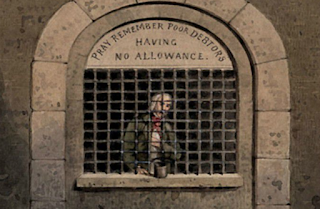

The problem in Scrooge’s day was that under common law, owners were jointly and severally liable for all debts of the business enterprise, regardless of the percentage of ownership held or the wealth or lack thereof of the owner. That meant that if the business went under, the creditors could sue the owners to try and get their money back and send any or all who failed to pay to debtor’s prison.

For example, suppose a business went bankrupt and owed £10,000 to the creditors, but the owner of the business had only £100 once all his assets were liquidated. Off he would go to Marshalsea Prison if the creditors so decided.

Let us further suppose that the bankrupt owner had given his twenty employees each a shilling bonus out of profits as a Christmas gift, a total of £1. In the eyes of the law, that made those employees co-owners of the business. The creditors could seize whatever assets those employees had (such as their life’s savings for retirement or next month’s rent), and if it did not satisfy the debt — and there was no way it could — send them off to join their former boss in prison, leaving their wives and children to starve in the street.

Obviously, no business owner with a shred of human feeling was going to put his employees at that kind of risk. Thus, in Scrooge’s fictional world as well as in the real world of Dickens, the whole force of society, individual, social, financial and institutional, was structured in a way that not merely inhibited Scrooge from being able to do the best thing for Bob Cratchit, it made it absolutely impossible for someone with any sense of justice or charity to do any such thing.

Some people, however, were aware of these problems, and were working on solving them, as we will see in the next posting on this subject.

#30#