As we saw in the previous posting on this subject, life in the early nineteenth century had thrown a lot of curves at most people in the form of massive social, economic and political change, and the institutions of the social order were not keeping up. Instead, radicals were calling for the abolition of all old institutions, such as private property, organized religion, and marriage and family, and their replacement with what was called by many names, but with one substance: socialism.

Socialism, however, is based on a theory of society and of human nature that is directly contrary to reality. It assumes as a given that an abstraction created by human beings has rights that human beings created by God do not. This means that human beings are more powerful even than God since they can do what God cannot . . . so why were things so bad?

According to the socialists, it was because people were going against real human nature, which is to be a member of the human race without being a full (or even partial) individual at the same time. The needs of individuals or of minorities could be sacrificed for the presumed greater good of the whole.

|

| Robert Owen, socialist-capitalist |

What about the capitalists? Surprising many people, capitalism and socialism are not as far apart as we have been led to believe. The first socialists were also capitalists, such as Robert Owen and Friedrich Engels. There were (and are) somewhat different assumptions underlying socialism and capitalism, of course, but these don’t really make for much of a difference when all is said and done. Still, and for example, where the Catholic Church has consistently condemned socialism, is has “only” criticized capitalism.

This is because where socialism insists that certain rights such as private property are held by no one by nature (which ultimately abolishes natural law in all respects), capitalism insists that only certain people effectively have all rights . . . which ultimately abolishes the natural law in all respects. Same end, different means. Both socialism and capitalism reject the natural law, that is, the concept of inalienable natural rights held in their fullness by every member of the human race.

|

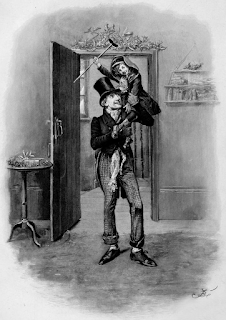

| Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim |

Almost as bad in a different way (because it gave the illusion of doing the right thing) was the response of people like Charles Dickens and — of course — one of his greatest fictional creations: Ebenezer Scrooge. The best they could do was to try and do what had always been done, only do it better, more justly, and certainly more charitably. Despite the success of Scrooge’s completion as a full person and initiation as full member of the human race, it was only possible due to the fact that Scrooge was fortunate enough to live in a fictional world where (assuming the author let you get away with it), good things would happen to people who were good. Bad things might happen to good people, but it could all work out in the end. If the author so decided, of course.

Dickens didn’t worry about seriously flawed institutions, such as money and credit or even advancing technology, which made his fictional world work so well, as least after the spirits set it aright. The real problem afflicting Scrooge, Cratchit, and countless others in the real world, therefore, was a bit more complicated.

|

| Adam Smith |

As technology advances, human labor becomes less valuable relative to capital as an input to production. Absent advancing technology, as Adam Smith explained in his “invisible hand” argument, even the greediest rich man can’t gratify his wants and needs without employing the poor. Somebody has to work the land, spin and weave, cook food, serve it, and clean up after. As a result, in a low-tech economy, wealth ends up being equitably distributed just as if private property had been equitably distributed.

What happens, however, when the rich can satisfy their wants and those of everyone else without employing the poor? What if advancing machinery displaces human labor so that with very little direct human input, owners of capital become hyper-productive in comparison to owners of mere labor?

The Financial Revolution of the late seventeenth century and the Industrial Revolution of the mid-eighteenth century had between them created an untenable situation. A relatively few people owned immense productive capacity and consumed almost nothing in proportion to what they produced, while the vast bulk of people owned virtually no productive capacity relative to the owners of capital, but had consumption needs vastly greater than their own capacity to produce.

|

| Dickens creating fictional worlds. |

As a result, owners of labor got less and less, while owners of capital got more and more — the rich got richer, while the poor in many cases got nothing. Instead of the non-owning classes being divided into the working poor who received wages, that were becoming insufficient to provide a decent living, and paupers who were destitute because they were unable or unwilling to work, more and more people were finding it next to impossible to find work of any kind as machines took over the burden of productive activity.

Thus, Dickens and other reform-minded people with a traditional Christian orientation could see the effects of the change, but tended to blame it on individual greed, selfishness, or whatever. They failed to see that something was going wrong with the system itself.

True, Scrooge, not the system, was clearly responsible for his own behavior, except in a very general and indirect way. Scrooge paid Bob Cratchit a just, market-determined wage, but that did nothing to change the fact that the replacement of labor with technology was lowering wages throughout the entire economy.

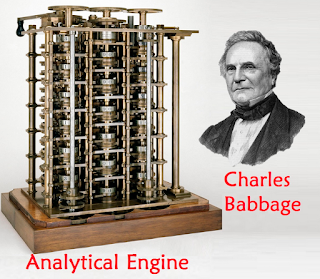

For his part, Cratchit was in no danger of being replaced by Charles Babbage’s proto computer (the “analytical engine”) — that would take another hundred and fifty years — but he was still up against the laws of supply and demand. Losing one’s position had become more than an annoying inconvenience with the prospect of a tedious search for a new job. It was now a terror-inducing threat tantamount to a death sentence. Cratchit put up with the unreformed Scrooge because the alternative was worse.

When Scrooge fulfilled and completed justice with charity and raised Cratchit’s salary, he saved not just Tiny Tim’s physical life, but Bob’s and his whole family’s lives from a dark cloud of daily horror and fear that was killing them as surely as Tiny Tim’s disability was killing him. Dickens may in fact have intended Tiny Tim in part as a metaphor for how hopeless poverty kills both soul and body, and how easily a little charity (and not just almsgiving) can save both.

That, however (as we will see in the next posting on this subject), did not address the underlying systemic problem.

#30#