Recently we came across a website purporting to be advocating “integralism,” which is a much-misused term for integrating one’s religious beliefs or philosophy into one’s daily life, the opposite of compartmentalization or schizophrenia. This was a “Catholic” website and was rather blatant about demanding that the civil power be subordinated to the religious power (meaning the Catholic Church) in all things . . . suggesting they didn't have a clue about real integralism; they could have stepped right out of a Thomas Nast cartoon.

In these “integralists’” view, American government is the deadly enemy of the Catholic Church . . . which claim actually justifies anti-Catholic propaganda and the idea that “good Catholic” and “good American” are not compatible terms.

The website — or, more accurately, the people running it — was, of course, dismissive of what it called liberalism and democracy without being too clear on what they are, other than they are something really, really, bad. In effect, what they seemed to be calling for was a Catholic theocracy, which is itself a really, really, really, bad idea.

The most obvious problem is what happens to the six billion or so people who don’t happen to be Catholic, or even Christian? What about all the Catholics who don’t go along with the whole theocratic notion? What about those who do go along with it, but object to whoever happens to be pope at the time? What about the pope? What if he objects?

Well, we know what happened when one pope objected. When Hugues-Félicité-Robert de Lamennais proposed his “theory of certitude” that (among other things) put the pope in the place of absolute ruler of the world, Pope Gregory XVI issued Mirari Vos, the first social encyclical, condemning de Lamennais’s ideas, calling his version of liberal democracy a “novelty.” De Lamennais, by the way, then renounced Christianity and founded his own religion. He later became known as the first modernist.

The problem is not liberal democracy per se, however, but the particular version radicals such as de Lamennais proposed. According to them, mankind in general is sovereign, not any individual.

Ironically, the Catholic Church is not the “enemy” of American liberalism, but virtually its sole remaining advocate — if we understand “democracy in America” as described by Alexis de Tocqueville in the early nineteenth century.

De Tocqueville identified three forms of liberal democracy prevalent in the 1830s. There was “French” or collectivist liberal democracy in which the abstraction of humanity is sovereign, and whoever controls the state does so in the name of the People. Then there was “English” or individualist liberal democracy, in which every person was nominally sovereign, but only an elite had an extra something that made sovereignty effective. Some thought it was “blood” or heredity, while others thought it was wealth.

Finally, there was “American” or personalist liberal democracy, in which the human person was sovereign and recognized as such. This is what do Tocqueville saw in the United States, although in a flawed application due to slavery and treatment of native peoples. This is the type of sovereignty Pope Pius IX, who appears to have been familiar with de Tocqueville’s work and may have corresponded with him, embodied in “the Fundamental Statute,” his constitution for the Papal States . . . which was overthrown by the radical, collectivist liberals in the revolutions of 1848, and obliterated by the individualist liberals when Sardinia conquered the Papal States.

|

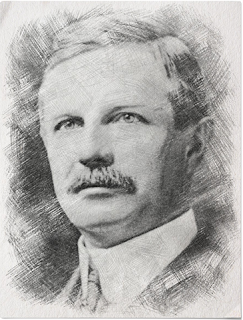

| Frederick Jackson Turner |

Unfortunately, as the American economy shifted from small ownership to the wage system and the “free” land available under the Homestead Act of 1862 was taken, America began the shift from personalist liberal democracy into the individualist and then collectivist variety, just as Frederick Jackson Turner noted in his “Frontier Thesis.” As a result, today’s “American liberalism” has virtually nothing in common but the label with what de Tocqueville saw in the 1830s and that Pius IX attempted to emulate in the 1840s.

Interestingly, some of John Locke’s anti-Catholicism may have been assumed for financial reasons. His patron was Lord Shaftsbury, the prime mover behind the Titus Oates “conspiracy,” and a violent anti-Catholic. Locke appears to have deliberately misrepresented Cardinal Bellarmine’s position on liberal democracy in his “First Treatise on Government.”

Fortunately, America’s Founding Fathers were more heavily influenced by Algernon Sidney in his “Discourses Concerning Government” who, while he missed a key element in Bellarmine’s thought (that man is by nature in society), declared he agreed with Bellarmine in everything except his religion, which he also claimed was not relevant to the discussion. It was probably George Mason of Gunston Hall who was responsible for correcting Sidney and basing the American form of liberal democracy on the “Catholic” understanding.

The natural law principles underlying American personalist liberal democracy are the same as those applied in Catholic social teaching, as we discuss in The Greater Reset: Reclaiming Personal Sovereignty Under Natural Law.

#30#