In the previous posting on this subject, we looked at what happened in the global financial markets as the result of the transformation of government debt from something people were forced into accepting, to a blue chip investment. Not only did this give government control over money and credit, it gave it as much other power as it could get citizens to accept by freeing governments from the necessity of having to ask the citizens for taxes.

A century later, the same thing gave rise to the move to take national currencies off fixed standards. As long as governments had to maintain parity of the debt-backed money with the standard, the government could not issue as much money as it wanted. It could only issue debt-backed money to the point at which any more would cause the value of the currency to deviate from the standard.

The dictatorships of the early twentieth century as well as the democracies faced with escalating social welfare costs and then the financing World War II were anxious to get rid of any adherence to a standard so they could spend more money. Paradoxically, it was one of the worst dictators who insisted absolutely on the inviolability of a fixed standard for the currency: Adolf Hitler. He had come to power partly driven by the fear of the German people that the hyperinflation of the early 1920s would return if order was not restored.

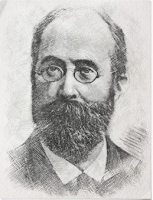

|

| Georg Friedrich Knapp |

By and large, however, by the early 1820s, governments were convinced that they could more or less safely back at least part of the currency with government debt. (It wouldn’t be until the 1880s when the socialist Georg Friedrich Knapp developed his “State Theory of Money” that the idea starting spreading that governments should back the entire money supply with government debt.)

Not unnaturally, this had some unexpected consequences. After all, had they been expected, they might have been avoided. . . .

With all the new countries coming into being in Central and South America, it was probably only a matter of time before somebody tried to take advantage of the situation, and in 1821 General Sir Gregor MacGregor, Knight of the Green Cross, Cazique of Poyais, and some other titles, not all of which were fictional, promoted the semi-fictional “Republic of Poyais” to British and French investors.

|

| General Sir Gregor MacGregor |

We say “semi-fictional,” because there was, in fact, land on the aptly named Mosquito Coast right where MacGregor said it was, and he may actually have persuaded a native chief (who might not have had the right to do so) to grant MacGregor title and sovereignty over the small territory. What was not there were the public buildings, infrastructure and private dwellings described in the brochure standing empty waiting only to be occupied by the settlers MacGregor recruited.

Brochures were not the only thing MacGregor printed. He also printed up government bonds, land certificates, and paper currency. Hundreds of people purchased the bonds and land certificates, and they were even traded on the London Exchange. Eventually he persuaded around two-hundred and fifty people to pack up and leave England and move to Poyais.

Unfortunately, the facilities they had been promised simply didn’t exist in the virgin jungle they found awaiting them. Adding to the problem was that few, if any, of the settlers knew how to start from scratch and build a colony from the ground up. Most of them were small businessmen or farmers who knew nothing of woodcraft or even how to cut trees for lumber so they could build.

It turns out, for example, that pine trees cannot be cut and then floated downriver immediately. Instead, they have to sit while the sap drains out (or be drained before cutting), or they are heavier than water and will sink. Some of the settlers spent enormous effort cutting pines for the settlement, only to have all their work sink into the river.

Republic of Poyais One Dollar Note

Eventually more than half the settlers died before fifty or so managed to make their way back to England in 1823 (some of the others remained in Honduras or other British outposts). When the story was reported in the British newspapers, some of the survivors defended MacGregor, claiming it had all been the fault of the incompetent leadership MacGregor had appointed.

Undeterred by the failure, MacGregor tried virtually the same scheme in France in 1826, whereupon he was arrested with three associates and charged with fraud. One of his associates was convicted, but MacGregor was acquitted, whereupon he went back to London and tried the same thing a few more times before moving to Venezuela in 1838, where he was given a hero’s welcome for his genuine accomplishments during the South American revolutions. He died in 1845 and was buried in Caracas Cathedral with full military honors.

As for the financial instruments Macgregor issued, the collapse of the colony made the bonds and land certificates worthless. The collapse helped trigger the Panic of 1825, considered the event that started the modern business cycle of “boom and bust.”

#30#