In the previous posting on this subject, we saw that even if ordinary people had sufficient savings during the Industrial Revolution, or even if they had gained access to the commercial and central banking system in England, broad-based ownership of the new industries would have been much too risky under the law of the time to allow it.

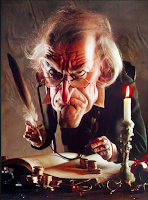

Any participation in ownership — and “ownership” was defined very broadly in those days — made someone a partner in the business and therefore jointly and severally liable for all debts of the corporation. If anything went wrong and the business went bankrupt, any and all owners could go to debtor’s prison, to be held there until the debts were repaid in full. An honest employer (and keep in mind that Ebenezer Scrooge was absolutely honest before and after his completion as a person) would not have put his employees at that kind of risk, even if (as Dickens put it) he was the most “squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner” on Earth.

|

| You Know Who |

Of course, being (pre-completion) “[h]ard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster,” it wouldn’t have occurred to him to share ownership before completion as a person, and certainly not afterwards when the thought of the danger he would be putting Bob Cratchit in would have appalled him. There was also the problem that, being strictly honest and a just man, even the reformed and completed Scrooge would have expected Cratchit to buy his partnership share — and even with Bob’s increase in salary, that was hardly likely, as the Cratchit family had many financial demands on it, and Bob had to save for retirement.

Nevertheless, one problem was about to be solved and a barrier to widespread ownership removed. There was a growing movement at the time Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol to extend limited liability to all corporations, not just those specially favored by the Crown or by parliament, e.g., the East India Company that owned large portions of the Indian subcontinent until the Great Mutiny of 1857, when it was turned over to direct rule by the British Crown and Queen Victoria (eventually) became Empress of India, after a short delay of twenty years or so.

|

| Louis Blanc |

What seems to have been particularly persuasive in extending limited liability to all corporations in Great Britain was a book by an investment banker by the name of Charles Morrison, An Essay on the Relations Between Labour and Capital (1854). What’s particularly interesting about Morrison’s book is that it is considered a milestone in the development of capitalism (which, in fact, it turned out to be), but Morrison’s goal was to eliminate capitalism!

To explain, the term “capitalism” wasn’t used in its modern sense until around 1850 by the French socialist politician and historian, Louis Blanc. As Blanc declared in Organisation du Travail (1851), “What I call ‘capitalism’ that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others.” Blanc, by the way, advocated State-owned but worker-controlled cooperatives, foreshadowing the syndicalism that got a bad name during the Paris Commune and the guild socialism that replaced syndicalism as the preferred term after that bloodbath.

|

| Thomas Malthus |

While accepting Malthusian theories (already discredited by a number of authorities whom Morrison and others ignored), Morrison for some reason disagreed with many other Malthusian experts of his day by insisting that the lot of the wage worker (“the working poor,” as they used to call them) was not hopeless — but there was a significant barrier in place that prevented employers from increasing worker compensation.

By “compensation,” Morrison definitely did not mean wages. As far as he was concerned, wages were being forced down by increasing population. With the supply of labor increasing, and the “wage fund” remaining constant, at least on an annual basis, wages were going to go down, no matter what anyone could do — if (and only if) “compensation” for workers was limited to wages.

|

| David Ricardo |

To explain, the “Wage Fund Doctrine” comes from David Ricardo's and Karl Marx's distortions of Adam Smith's theories. It is the belief (based on the Malthusian faith, so the term “doctrine” is appropriate both religiously and in the sense of “something that is taught) the amount of money a worker earns in wages, paid to them from a fixed amount of funds available to employers each year (capital), is determined by the relationship of wages and capital to any changes in population. Thus, as the “supply” of workers increases, wages go down, and as the supply goes down, wages rise. This, of course, is a “past savings” assumption that completely ignores the possibility that an employer may borrow working capital to pay workers more, capitalize the labor used in product development, or find a means other than wages to compensate workers.

|

| Non-Owning Worker Woes |

And that is precisely what Morrison came up with — a way to compensate workers without trying to increase wages: profit sharing. As Morrison argued, because wages must necessarily fall as population increases, they must add ownership income to labor income, or face starvation. As we have seen, however, under then-current British law, the gradual and not completely certain starvation of the wage worker and his family was preferred over the certain disaster if the worker were to be thrown into prison for the debts of the corporation.

The only answer, as Morrison saw it, was to extend limited liability to all corporations so that employers could pay workers more out of profits instead of going against iron Malthusian constraints that prevented wages from rising. Increasing compensation out of profits would not increase business costs and would also inspire workers to greater efforts as part owners of the business. They would know that the harder they worked and the more they produced, the better off they and everyone else would be.

This, in fact, was the same argument labor-stateman Walter Reuther made a little over a century after the publication of Morrison’s book. As Reuther testified before the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, February 20, 1967,

|

| Walter Reuther |

The breakdown in collective bargaining in recent years is due to the difficulty of labor and management trying to equate the relative equity of the worker and the stockholder and the consumer in advance of the facts…. If the workers get too much, then the argument is that that triggers inflationary pressures, and the counter argument is that if they don’t get their equity, then we have a recession because of inadequate purchasing power. We believe this approach (progress sharing) is a rational approach because you cooperate in creating the abundance that makes the progress possible, and then you share that progress after the fact, and not before the fact. Profit sharing would resolve the conflict between management apprehensions and worker expectations on the basis of solid economic facts as they materialize rather than on the basis of speculation as to what the future might hold…. If the workers had definite assurance of equitable shares in the profits of the corporations that employ them, they would see less need to seek an equitable balance between their gains and soaring profits through augmented increases in basic wage rates. This would be a desirable result from the standpoint of stabilization policy because profit sharing does not increase costs. Since profits are a residual, after all costs have been met, and since their size is not determinable until after customers have paid the prices charged for the firm’s products, profit sharing as such cannot be said to have any inflationary impact upon costs and prices…. Profit sharing in the form of stock distributions to workers would help to democratize the ownership of America’s vast corporate wealth.

|

| Not amused, but signed it anyway. |

Morrison’s book seems to have been decisive in the ongoing debate over allowing limited liability to all corporation, although some in parliament continued to maintain that extending it to everyone was irresponsible and would encourage reckless behavior. Nevertheless, others maintained that people would become more productive if they were assured they wouldn’t go to prison if things turned out badly. On August 14, 1855, then, Queen Victoria gave the Royal Assent to the Limited Liability Act 1855 (18 & 19 Vict c 133), the first allowing limited liability for corporations that could be established by the general public.

There still remained a problem, however, and it was fatal. Given that virtually all the experts in 1855 believed that it is impossible for anyone to finance new capital acquisition except by not consuming all of one’s income, how was worker ownership to be financed when wages were falling, and raising wages would only cause inflation by increasing costs, making the workers worse off than before?

That is what we will look at in the next posting on this subject.

#30#