Recently an article appeared on Catholic World Report, “Catholics and Race in American History,” the point of which seemed to be to excuse a presumed lack of action by the Catholic Church in failing to condemn slavery while it was legal, and present a sterling record of condemning racism ever since. The problem with the article was that it missed certain things that would have made the institutional Catholic Church look a lot better than it did, while making individual Catholics look a lot worse.

Primarily — and it is puzzling why this was not mentioned — there was the incident that has caused anti-Catholics to howl with glee (e.g., Mark Twain), and Catholics to react with shame and confusion. In 1838, the Jesuits of Georgetown University organized one of the largest slave auctions in U.S. history to finance the institution.

What most people don’t know is that, directly as the result of this action, a year later Pope Gregory XVI issued the encyclical In Supremo condemning slavery . . . whereupon the U.S. Southern bishops hastened to reassure their flocks that the pope’s condemnation did not apply to slavery as practiced in the United States. This was despite a few centuries of official condemnation and discouragement of slavery, as chronicled in Rev. Joel S. Panzer’s book, The Popes and Slavery (1996).

The reaction of the bishops was hypocritical, perhaps, and certainly self-serving. It is, however, not really any different from the present day when a significant number of bishops promote various forms of socialism and moral relativism, insisting that they are consistent with what the Catholic Church teaches despite two centuries of explicit condemnation.

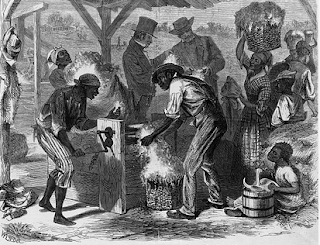

Another thing that most people don’t know is that slavery in the United States was on the way out in the late eighteenth century . . . and then the cotton gin was invented. Suddenly cotton went from a luxury fiber to a low-priced staple. Prior to the cotton gin, all fiber was relatively expensive and difficult to produce, whether wool, linen, silk, or anything else.

|

| Mills of Manchester: an insatiable demand for cotton |

For the first time in history there was an affordable and plentiful source of fiber. Production soared. From 1803 to 1937 cotton was the single largest export from the United States. Demand for more land and slaves to produce cotton was the primary political motive that drove U.S. domestic policy in the first half of the nineteenth century when the agrarian South controlled Congress.

The desire to expand production of cotton led to the removal of the Cherokee and the Trail of Tears, “Bleeding Kansas,” and in 1855 the book that probably did more to cause the Civil War than any other — and it wasn’t Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. No, it was David Christy’s Cotton Is King, in which Christy, a former abolitionist, argued that the economic survival of the United States and of the British Empire depended absolutely on U.S. slave-cultivated cotton.

|

| Dred Scott |

Two years later, pro-slavery forces won what they considered their greatest victory: the decision in Scott v. Sandford — the notorious Dred Scott case — which effectively overturned the natural law basis of the U.S. Constitution and made slavery de facto legal everywhere in the country. According to Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, a Catholic with modernist and socialist (“Neo-Catholic”) leanings, all rights come from the State, and a black man has no natural right to liberty or anything else unless so granted by the State.

Legal history usually explains that what Taney argued was that Dred Scott could not be a citizen, but Taney’s argument was a little more involved than that. Conflating the terms “citizen” and “person,” Taney claimed that since the State grants citizenship where it will, it also grants personality — a claim directly contrary to millennia of natural law theory, but which forms the basis of socialism and modernism.

|

| Roger Brooke Taney |

In classic Aristotelian-Thomist natural law theory, God builds natural and absolute rights of life, liberty, and private property into each individual human being. The exercise of natural rights, however, is socially determined and is necessarily limited and defined by the State. Taney’s argument confused natural and absolute rights with their necessarily limited and State-defined exercise, thereby asserting that definition and limitation were the same thing as creating and vesting.

Thus, in Taney’s line of reasoning, the State grants both natural rights (thereby creating persons) and defines their exercise (civil rights and citizenship). Inalienable rights of life, liberty, and private property became alienable if the State so decreed.

|

| Hegel: "The States is as a God." |

Taney’s position is the basis of both socialism and modernism, in which the collective, an abstraction created by human beings, becomes more powerful than human beings created by God. This means that Collective-Man-as-God replaces the concept of God found in traditional natural and revealed religions. God becomes perceived not as a transcendent and supreme Being, but as a sort of “divinized society” that is constantly evolving, as Fulton Sheen put it (Fulton J. Sheen, Religion Without God. New York: Garden City Books, 1954, 54); religion is transformed into the group’s worship of itself (Joseph A. Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954, 794).

The Dred Scott decision was overturned by the 14th Amendment, but the 14th Amendment was almost immediately nullified by the Supreme Court’s decision in the Slaughterhouse Cases of 1873, which eventually led to Roe v. Wade in 1973.

It can therefore be argued that racism didn’t lead to slavery, slavery led to racism — for economic reasons. That is why a group in St. Louis, “Descendants of American Slaves for Economic and Social Justice,” founded and led by Eugene Gordon, insists that reparations for slavery and an end to racism require not handing out cash or affirmative action, but opening up economic opportunity and access to the means of acquiring and possessing private property in capital to all people, not just descendants of slaves, but to descendants of slave owners and everyone else as well. This could be done with the Economic Democracy Act. Gene says we must learn from the past, not live in it.

#30#