At the end of the previous posting on this subject, we

noted that some people with agendas had found what they wanted in John Henry

Newman’s book, An Essay on the

Development of Christian Doctrine. The

problem was that what they claimed to have found was the opposite of what

Newman had actually written.

Nevertheless, religious doctrine (Christian or otherwise)

is not our affair. Our interest is social

doctrine, which pertains to the natural law, not to revelation.

Revelation pertains to the supernatural world,

not the natural world, although this discussion

employs religious terminology and is generally framed within

the parameters established for religious society.

|

| John Bernard Fitzpatrick |

Just before the controversy arose regarding what Newman

meant in his book, Bishop John Bernard Fitzpatrick of Boston (1812-1866) had with

some reservations received Orestes Brownson into the Catholic Church. Perhaps as a test of the new convert’s

devotion and obedience, Fitzpatrick encouraged Brownson to critique Newman’s

concept on the development of doctrine.

A number of U.S. bishops, Fitzpatrick among them, were of

the opinion that because variation and change in doctrinal matters were

characteristic of Protestantism, development of doctrine was the equivalent of

change and variation and therefore itself an error. (Carey, Orestes

Brownson, op. cit., 171.) The fact

that Brownson’s own — temporarily — repudiated “Doctrine of Communion” which he

had derived from the thought of the socialists Henri de Saint-Simon (1760-1825) and Pierre

Leroux (1797-1871) resonated reasonably well with Newman’s concept of the

development of doctrine only served to convince Brownson that the American

bishops had read the situation accurately.

As far as Brownson was concerned, Newman’s concept was not merely

Protestant, but socialist. (Ibid., 97-133.)

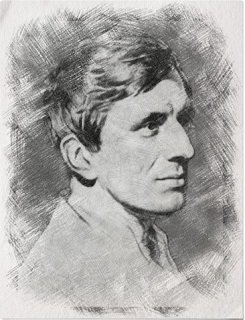

|

| John Henry Newman |

Brownson’s usual irascibility combined with the militant

fervor of a new convert, and he set to work.

For two-and-a-half years the battle raged until the American bishops, now

uneasy over the situation they themselves had in large measure created and that

was taking on the nature of a scandal, managed to persuade Brownson to drop the

issue of “Developmentism” — for a while.

(Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Orestes

A. Brownson: A Pilgrim’s Progress.

New York: Octagon Books, Inc., 1963, 202.)

As had quickly became evident to thoughtful observers,

however, the real difference between the two was not in what they said, but in

their respective approaches to apologetics.

Both Newman and Brownson, of course, sought the truth. Where Newman had taken the approach dictated

by his background and experience and stressed the similarities among the different

forms of Christianity, however, Brownson was equally formed by his background

and experience and targeted the differences among the various sects.

|

| Isaac Thomas Hecker |

Both men, therefore, were of essentially the same mind and

in fundamental agreement about the teachings of the Catholic Church, but each

was taking a diametrically opposed road to truth — in form, that is, not in

substance. Newman did not really care

whether he won an argument as long as he persuaded someone, while Brownson, as

his friend Father Isaac Hecker noted, could defeat an opponent, but never

convince him. (Joseph McSorley, Father Hecker and His Friends. St. Louis, Missouri: B. Herder Book Company,

1953, 221.) Newman, in fact, believed

that to be argumentative was to be irreverent.

(Chadwick, The Mind of the Oxford

Movement, op. cit., 47.)

Very, very briefly, Brownson, in common with those of the

U.S. bishops who took his side in the affair until it became too embarrassing

for them, confused revelation (which

comes from God) and doctrine (which is

developed by man from revelation), and even in some instances with discipline (a

specific policy or practice to implement doctrine).

To explain, revelation is the unchanging general principle,

while doctrine consists of specific interpretations of revelation and must

develop if people are to be able to continue their faith journeys as knowledge of

this world and of the human condition expands and deepens. Where revelation is the general truth,

doctrine is a particular principle, statement, or position that is taught or advocated to apply truth to a

specific set of circumstances.

|

| Christ came to fulfill the Law of Moses |

This needs to be taken one step

further, into the area of discipline,

or man-made regulations by means of which doctrine is actually and formally implemented

or a group handles administration of itself.

Thus, revelation must be consistent with what people believe about God

and at the same time not contradict reason, doctrine must be consistent with

revelation, while discipline can be anything that does not contradict doctrine.

Again, our concern here is not religious doctrine, however,

but social doctrine. Examining the specific

theological issues that divided Brownson and Newman in any depth is far, far

beyond the scope of this study, and would serve no useful purpose in any event. The simple fact is that the major Christian

bodies have from the beginning accepted the validity, even the necessity of

doctrinal development, e.g., Christ’s

declaration that He came to “develop doctrine” by fulfilling the Law of Moses,

not abolishing it.

So why even bring it up?

Because it might explain in part why the concept of social justice was

so easily hijacked by the socialists, modernists, and New Agers in what was

arguably the most democratic and genuinely liberal country on Earth — the

United States of America.

|

| Opening of the First Vatican Council |

Brownson’s notion of the infallibility of the Catholic

Church (formed decades before the formal definition of the infallibility of the

teaching office of the pope at the First Vatican Council) was that all Catholic

doctrine — which he considered the same as revelation — was as unchangeable as

it was free from all error, and vice

versa. That this bears little

resemblance to the doctrine of infallibility as defined by the Council Fathers

mattered little to Brownson, even as he firmly believed that what the Council

defined was fully consistent with what he believed. That is because, in common with many people

even today, Brownson simply assumed that his understanding of a doctrine was

the only possible one.

Thus, the institutions (doctrines) of the Catholic Church

were not merely free from error, but also not subject to change or

“development” of any kind. To admit that

doctrine could “develop” was to Brownson tantamount to an admission that it was

not perfect. As far as Brownson was

concerned, Newman was therefore a Protestant.

(Brownson changed his mind later, after the damage had been done.)

|

| Orestes A. Brownson |

Similarly, in the civil sphere American institutions were

perfect, precisely as the Constitution proclaimed. Why else would the Preamble to that document

have referred to “a more perfect union”?

(Brownson’s complicated rationalizations of the chattel slavery he detested but

needed to fit within what he believed to be a perfect system are . . .

interesting.)

As something of a Platonist, Brownson saw the duty of the

citizen to conform himself to his institutions, not to modify those

institutions to conform to human wants and needs within the broader parameters

of the natural law. Brownson’s opinion

of amendments to a constitution is not clear, although there had been fourteen

added to the U.S. document since its adoption by the time of his death. As he declared in what many consider his

greatest work, The American Republic

(1865) — and incidentally letting slip a bit of his Anglophobia,

The English are great constitution-mongers — for other

nations. They fancy that a constitution

modeled after their own will fit any nation that can be persuaded, wheedled, or

bullied into trying it on; but, unhappily, all that have tried it on have found

it only an embarrassment or encumbrance.

The doctor might as well attempt to give an individual a new

constitution, or the constitution of another man, as the statesman to give a

nation any other constitution than that which it has, and with which it is

born. (Orestes A. Brownson, The

American Republic: Its Constitution, Tendencies and Destiny. Wilmington, Delaware: ISI Books, 2003, 100.)

Unfortunately for Brownson’s opinion and the new field of

social justice (in the 1840s the term was just coming into use in the Catholic

sense, and then only vaguely), the task of any member of society when his

institutions do not meet his needs and those of his fellows is not to change

human nature. Rather, it is to organize

with others to change his institutions.

Reforming institutions is not only permissible, but

essential if institutions are to continue to be useful social tools instead of

barriers to full human development. The

caveat with any civil institution, of course, is similar to that of religious

institutions (doctrines): the underlying principle must never be violated, i.e., revelation in the case of a

religious doctrine, the natural law and respect for essential human dignity in

the case of a civil institution.

Institutions and doctrines must grow and develop, not

remain static, as long as they remain consistent with the original principle. Newman, the individualist and solitary

scholar, somehow understood this rule.

Brownson, who had developed a theory that came close to solidarism, did

not.

And that is the paradox we will look at in the next

posting on this subject.

#30#