One of Pope John Paul I’s expressed concerns as Patriarch

of Venice was the plight of the poor.

His first “letter” in Illustrissimi,

in fact, is to Charles Dickens, and at first glance seems to be a standard

semi- or full-socialist condemnation of the evils and greed of capitalism, the

free market, the dictators of money, and so on, so forth.

The letter to Dickens is, however, much more profound than

the usual socialist interpretation would have us believe. As we saw in the previous posting in this series, many (if not most) people think that Catholic social teaching is about

garnering more and more material benefits for the poor.

|

| Daniel Webster |

That is correct in a sense, but the material benefits

sought as the results of effective application of Catholic social teaching are

not increases in wages, benefits, and welfare, but the very material and

beneficial power over one’s own life.

For that reason, widespread private property in capital is essential,

because (as Daniel Webster noted) “Power naturally and necessarily follows

property.”

That being said, however, pay close attention to what was written

above: we did not say that Catholic social teaching means securing material

benefits of any kind. Very much the

contrary! Catholic social teaching has

as its goal institutional reform to make it possible

for people to secure material, social, and even spiritual benefits through

their own efforts, not to have such things simply distributed to them because

they need them.

Individual goods such as private property and even wages,

benefits, and welfare, regardless how

many people receive them, are, have always been, and will always be individual. As Pope Pius XI explained in § 76 of Quadragesimo Anno,

What We have thus far stated regarding an equitable

distribution of property and regarding just wages concerns individual persons

and only indirectly touches social order, to the restoration of which according

to the principles of sound philosophy and to its perfection according to the

sublime precepts of the law of the Gospel, Our Predecessor, Leo XIII, devoted

all his thought and care.

Still, at first glance the letter to Dickens strikes the

reader as very socialist, indeed! It

also sounds very much as if John Paul I was strongly in favor of what is

variously known as syndicalism or guild socialism, i.e., some kind of diffused socialism with the economy controlled

at the local rather than the national level.

As he wrote,

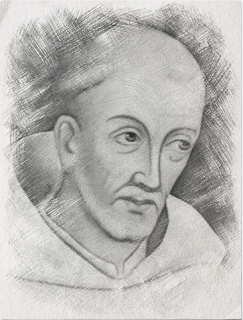

|

| Pope John Paul I |

You must be curious to know if and how some remedy has been

found for the situations of poverty and injustice that you reported.

I will tell you at once.

In your own England, and in industrialized Europe, the workers have

greatly improved their position. The

only power they could command was their numerical strength. They exploited it. . . .

The workers, at first separate and scattered grains of sand,

have become a compact cloud, in their unions and in the various forms of

socialism, which have the undeniable merit of having been, almost everywhere, the

chief cause of the workers’ upward rise.

Since your day, they have advanced and achieved much in the

areas of economy, social security, culture.

And today, through the unions, they often manage to make their voice

heard still higher, in the upper ranks of the government where, actually, their

fate is decided. (Luciani, Illustrissimi, op. cit., 5-6.)

This apparent paean in praise of socialism sounds pretty

good. Many people would conclude from it

that John Paul I was crediting socialism with greatly improving the lot of the

workers. They would also feel justified

in assuming that the future pope was going even further and actually advocating

socialism as the solution to the problems of the modern world.

|

| Charles Dickens |

That is, many people would assume that is what John Paul I

was saying if they did not realize the import of the subsequent paragraphs. Having apparently praised socialism and the

labor movement to the skies, he suddenly changes tone and begins listing the

problems of the modern world that, somehow (and a little unfairly) he made

sound as if they were worse than those of the nineteenth century.

And what of now? Alas!

In your time social injustices were all in one direction: against

workers, who could point their fingers at the boss. Today, a vast array of people are pointing

their fingers. . . . Many workers are unemployed or fear for their jobs. They . . . feel treated as mere tools of

production and not as human protagonists. . . . Fear and concern are

great. For many the desert animal to be attacked

and buried is no longer only capitalism, but also the present “system,” to be

overturned with a total revolution. For

others the process of overturning the system has already begun. (Ibid., 6-7.)

Far from uniting people, then, the race to establish and

maintain the goal of religious or democratic socialism — the Kingdom of God on

Earth — has only led to greater alienation and anger. Where once the poor felt powerless against

the capitalist, they now feel powerless against “the system” that is failing in

the attempt to take care of everything.

The spiritual malaise that called socialism into being in the first

place is now worse than ever before.

Ironically (for it is clear that John Paul I was familiar

with Rerum Novarum), he had the

theoretical answer to the problem of social alienation: widespread capital

ownership. What he did not have was a

practical means of attaining the very remedy that Leo XIII advocated.

|

| Saint Bernard of Clairvaux |

What he did have was a realization that obsessing about applications

to the exclusion or even contradiction of the underlying principles was

virtually a guarantee of ineffectiveness, especially in the area of social

justice. Calling to mind Pope Benedict

XV’s reminder at the beginning of World War I that we must always do “old

things, but in a new way” (Ad Beatissimi

Apostolorum, § 25), John Paul I chastised those who latch on to a single

application or assumption without regard to anything else in his letter to

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux by condemning —

. . . the attitude of those who stubbornly refuse to face

evident realities and fall into excessive rigidity and integralism, becoming

more monarchist than the king, more papist than the pope.

This happens. There

are those who, having mastered an idea, bury it and continue to preserve it, to

defend it jealously for their whole lives, never reexamining it, never checking

to see what it has become after so much rain and wind, after the storms of

events and changes.

Those who travel in the stratosphere run the risk of not

being prudent, and, crammed with purely bookish learning, they cannot once move

away from what is written, real nitpickers always intent on analyzing, taking

to pieces, always in search of hairs to split. (Ibid., 36.)

Note that John Paul I was not condemning integralism per se, “integralism” being the

integration of all aspects of life into the precepts of the Gospel and the

Magisterium (teaching authority of the Catholic Church). Rather, he was commenting on excessive integralism, the exaggeration

of one aspect of Catholic teaching to the exclusion of all else, making everything

subordinate to one thing.

|

| Pope John Paul II |

Not surprisingly, John Paul II also commented on this

tendency in 1999 when he chastised the bishops of North and South America for

driving people out of the Church by exaggerating one part of Catholic social

teaching. As he declared, pointing out

that enthusiasm for one thing to the exclusion of others is contrary to the

very Gospel they were supposed to be spreading,

As I have already noted, love for the poor must be

preferential, but not exclusive. The Synod Fathers observed that it was in part

because of an approach to the pastoral care of the poor marked by a certain

exclusiveness that the pastoral care for the leading sectors of society has

been neglected and many people have thus been estranged from the Church. The

damage done by the spread of secularism in these sectors — political or

economic, union-related, military, social or cultural — shows how urgent it is

that they be evangelized, with the encouragement and guidance of the Church's

Pastors, who are called by God to care for everyone. They will be able to count

on the help of those who — fortunately still numerous — have remained faithful

to Christian values. In this regard the Synod Fathers have recognized “the

commitment of many leaders to building a just and fraternal society”. With

their support, Pastors will face the not easy task of evangelizing these

sectors of society. With renewed fervor and updated methods, they will announce

Christ to leaders, men and women alike, insisting especially on the formation

of consciences on the basis of the Church's social doctrine. This formation

will act as the best antidote to the not infrequent cases of inconsistency and

even corruption marking socio-political structures. Conversely, if this

evangelization of the leadership sector is neglected, it should not come as a

surprise that many who are a part of it will be guided by criteria alien to the

Gospel and at times openly contrary to it. (Ecclesia in America, § 67.)

Still, John Paul I had no effective means of going beyond

the usual expedients of wages, benefits, and welfare. Wisely or unwisely, therefore, he said

nothing, merely limited himself to calling for more solidarity and unity. These are good, even great words, but hollow

and empty without the power needed to make them meaningful.

The problem is that within the wage system, the presumed solution

is to raise wages in order to distribute sufficient income to clear

production. This raises the costs of

production, giving more incentive to capital owners to replace even more human

labor with technology, thereby requiring more increases in wages just to keep

up.

|

| John Maynard Keynes |

(There is an added problem with Keynesian economics. Within the Keynesian paradigm, new capital

formation requires that production exceed consumption in order to “save.” This means that more goods must be produced

than can be consumed . . . thereby setting up a “paradox of savings,” viz., that more must be produced than

can be consumed, but it cannot be turned into financing for new capital unless

it is consumed!

(Keynes’s solution was to inflate the currency, shifting

purchasing power from one group of people to another group of people; the idea

that inflating the currency “creates” purchasing power is, obviously,

nonsense. Inflation “robs Peter to pay

Paul,” decreases the costs of production by cheapening money, and raises

prices, thereby increasing profits to owners of capital and causing additional

demands for more inflation and redistribution.)

What is needed is a way to increase consumption income

without raising prices — and thereby benefit everyone instead of just those who

profit from inflation. Not just

materially, but by bringing “labor” and “management” together in a common

cause, laying the foundation for genuine solidarity.

And that is what Walter Reuther realized he had found in

Louis Kelso’s economic theories. As he

said in his testimony before the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, February

20, 1967, a few years before John Paul I wrote his letter to Dickens,

|

| Walter Reuther |

The breakdown in collective bargaining in recent years is due

to the difficulty of labor and management trying to equate the relative equity

of the worker and the stockholder and the consumer in advance of the

facts…. If the workers get too much, then the argument is that that

triggers inflationary pressures, and the counter argument is that if they don’t

get their equity, then we have a recession because of inadequate purchasing

power. We believe this approach (progress sharing) is a rational approach

because you cooperate in creating the abundance that makes the progress

possible, and then you share that progress after the fact, and not before the

fact. Profit sharing would resolve the conflict between management

apprehensions and worker expectations on the basis of solid economic facts as

they materialize rather than on the basis of speculation as to what the future

might hold…. If the workers had definite assurance of equitable shares in the

profits of the corporations that employ them, they would see less need to seek

an equitable balance between their gains and soaring profits through augmented

increases in basic wage rates. This would be a desirable result from the

standpoint of stabilization policy because profit sharing does not increase

costs. Since profits are a residual, after all costs have been met, and since

their size is not determinable until after customers have paid the prices

charged for the firm’s products, profit sharing as such cannot be said to have

any inflationary impact upon costs and prices.

That addresses the income question — but what about the

power issue? Reuther was prepared for

that as well. Power follows property,

therefore —

|

| Louis O. Kelso |

Profit sharing in the form of stock distributions to workers

would help to democratize the ownership of America’s vast corporate wealth

which is today appallingly undemocratic and unhealthy. The Federal Reserve

Board recently published data from which it is possible to estimate the degree

of concentration in the ownership of publicly traded stock held by individuals

and families as of December 1962. Preliminary analysis of these data indicates

that, despite all the talk of a “people’s capitalism” in the United States,

little more than one percent of all consumer units owned approximately 70

percent of all such stock. Fewer than 8 percent of all consumer units

owned approximately 97 percent—which means, conversely, that the total direct

ownership interest of more than 92 percent of America’s consumer units in the

corporation-operated productive wealth of this country was approximately 3

percent. Profit sharing in a form that would help to correct this shocking

maldistribution would be highly desirable for that reason alone.… If workers

had definite assurance of equitable shares in the profits of the corporations

that employ them, they would see less need to seek an equitable balance between

their gains and soaring profits through augmented increases in basic wage

rates. This would be a desirable result from the standpoint of stabilization

policy because profit sharing does not increase costs. Since profits are a

residual, after all costs have been met, and since their size is not

determinable until after customers have paid the prices charged for the firm’s

products, profit sharing as such cannot be said to have any inflationary impact

upon costs and prices. (Ibid.)

Unfortunately, John Paul I was not aware of what Reuther

said, nor of Kelso’s theories. What he

said about the need to develop solidarity and Christian values and so on was

and remains important, of course.

Regardless of one’s faith or philosophy, the whole meaning and purpose

of life is to become more fully human, which means acquiring and developing

virtue — “human-ness” — as long as that is consistent with basic human nature,

of course.

Acquiring and developing virtue, or doing anything else,

however, requires power, and the only legitimate, effective, and lasting power

comes from private property in capital.

And how to get capital ownership into as many people’s hands as possible

is what was missing in the thought of John Paul I, as well as other popes.

#30#