Just the other

day we were talking about what we would do if we were putting together a series

of educational videos or audio recordings or something like that. Naturally, there was no dearth of suggestions

about what to cover, e.g., “What is

Money?” (a personal favorite, not that you’d know it from reading this blog. .

. .), “What is Justice?”, “What is Private Property?” (are you detecting a

certain theme here?), and so on.

|

| Law #1 of the common good: you can't illustrate the common good. |

Part way through

the discussion somebody mentioned, “What is the Common Good?” as a possible

video. For some reason we hadn’t thought

of it before, but it’s a natural subject when you’re talking about economic and

social justice. Economic justice is a

type of social justice, and social justice is directed not at individual good

or goods, but at the common good.

So, what is the

“common good”? In a philosophical sense,

the common good of human beings consists of the “analogously complete” capacity

each and every human being has to acquire and develop virtue.

You didn’t need

that before you had your morning coffee, but all it means is that all human

beings are exactly alike — “analogues” — with respect to the thing that defines

us — and that means each and every one of us — as “human.” Every single human being is as fully human as

every other human in this respect, and is human in exactly the same way. No one is more human than anyone else, and no

one is less human.

This capacity to

acquire and develop virtue is the one good that every single human being has in

common with all other human beings. It

is therefore THE common good. It should

not — and must not — be confused with other things that some people think of as

the common good, but don’t meet the definition, for example —

·

The

aggregate of all individual goods.

Nope. It doesn’t matter how many

people there are. They remain

individuals, even if they are also members of a group. Each individual “owns” the totality of the

common good — not as he or she would own a car, a house, or a dog, but as he or

she owns life, and you aren’t less alive just because someone else is also

alive.

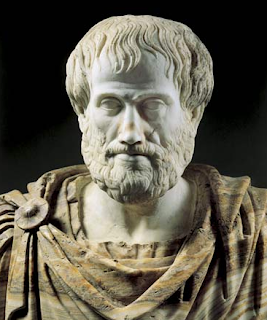

|

| Aristotle: easier to illustrate than the common good. |

That’s because,

in a sense, the common good is life —

social life, not individual life. That’s

because as “political animals” (as Aristotle described us) people ordinarily acquire and develop virtue

(individual habits) within a social context or environment, and that

environment consists of institutions or “social habits.” Only this vast network of institutions is

properly the common good, because in

order to become more fully human, each person needs access to those

institutions.

·

Goods

owned in common by the community, State, or business. Nope. Goods

owned in common are an expedient, not a necessity. Aquinas is very careful to warn people that

the common good is not common goods.

There is nothing that says roadways or any other infrastructure must be owned in common; even air and water

can be privately owned under some circumstances, e.g., a spaceship. Nor can

you do what you like with common goods.

You only get the use of common goods (and then only the proper use), you

do not actually possess them.

Possibly to make

things clear (or not), here is what CESJ co-founder Father William J. Ferree,

S.M., Ph.D., had to say about the common good in his pamphlet, Introduction to Social Justice:

The Nature of the Common Good

Every higher institution depends on all those below it for its

effectiveness, and every lower institution depends on those above it for its

own proper place in the Common Good. It is precisely this whole vast network of

institutions which is the Common Good, on which every one of us depends for the

realization of our personal perfection, of our personal good.

|

| Fr. William J. Ferree, S.M., Ph.D. |

It is wrong to conceive of the Common Good as a sort of general bank

account into which one “deposits” when, for instance he pays his taxes to the

State; and “withdraws” when he is appointed public coordinator of something or

other at a hundred and fifty dollars a week, or when the State builds a road

past his farm and thus raises its value. It is surprising how many people think

that distributive justice is the virtue that assesses taxes and Social Justice

is the virtue that pays them. Both of these actions are distributive, that is,

individual, justice; and become Social Justice only in a secondary way as they

promote the Common Good.

Nor must we think of the Common Good as something which we can “share

with another” like a candy bar or an automobile ride. Rather it is something

which each of us possesses in its entirety, like light, or life itself. When

the Common Good is badly organized, when society is socially unjust, then it is

each individual’s own share of

personal perfection which is limited, or which is withheld from him entirely.

Everyone Can Do It

When it is realized that the Common Good consists of that whole vast

complex of institutions, from the simplest “natural medium” of a child’s life,

to the United Nations itself, then a very comforting fact emerges: Each of

these institutions from the lowest and most fleeting “natural medium” to the

highest and most enduring organization of nations is the Common Good at that

particular level. Therefore everyone,

from the smallest and weakest child to the most powerful ruler in the world,

can have direct care of the Common Good

at his level. This is a far cry indeed from those social philosophers who

before Pius XI could say with complete sincerity and conviction, “the Common

Good is not something which can be directly

attained.”

Now, just why this

is important is something we’ll look at tomorrow.

#30#