One thing we’ve

noticed (i.e., had driven home to us

like a railroad spike through the skull) is that quite a large number of people

are confused about the difference between a general principle, and a particular

application of that same principle. Yet

all the sciences, moral philosophy, and even theology are based in some measure

on this distinction.

|

| Euclid: "Lessee, 2 + 2 = pons asinorum..." |

Take, for

example, the science of mathematics.

Euclid’s First Element is, “Things

which equal the same thing also equal one another.” Thus, if 1 + 3 = 4, and 2 + 2 = 4, then you

can be absolutely certain that 1 + 3 = 2 + 2, no ifs, ands, or buts. The general principle, “Things which equal

the same thing also equal one another,” is applied in the specific (or

“particular”) equations 1 + 3 and 2 + 2.

In moral philosophy, the universal

prohibition against theft, i.e., the general

norm of the natural law, “Thou shalt not steal” demonstrates that the right to

be an owner, “the right to private property,” comes under the natural law. Why? Everyone

everywhere knows that it is contrary to nature, i.e., “wrong,” to take what does not belong to you. This necessarily implies that private

property is a right by nature, or it would not be wrong to take what does not

belong to you.

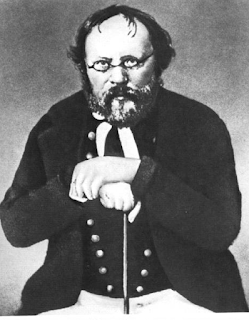

|

| Proudhon: "Property is theft ... except for my stuff." |

Proudhon’s “Property is

theft” means “property is a violation of property,” which is utter nonsense. All the socialist and redistributist

arguments ever advanced since humanity came down from the trees are based on

proving to the satisfaction of the thief that 1) the ostensible owner of what

the thief desires doesn’t really own, 2) because the thief is either the real

owner, or acting on behalf of the real owner.

The right to be an owner,

however, says nothing about any specific system of political economy. As long as the system respects the dignity of

each human person in a way that secures universal access to the means of

acquiring and possessing private property in capital, then it conforms to the

general norm of the natural law.

We won’t bother with an

example from theology. We’d first have

to make the case for the general principle, and then the application, and we’ve

already done enough with science and philosophy.

We can — and must — however,

deal with the natural right of liberty, also known as freedom of association or

contract, which is what started us on today’s brief journey into the murky

waters of logic . . . murky, that is, in a day and age that has pretty much

rejected reason as the basis for anything.

Freedom sounds very nice —

and it is. Under the name “liberty” it

is almost always included in the great triad of natural rights, life, liberty,

and private property.

|

| Jefferson: "Everyone has the right to be free ... except those I own." |

Yes, freedom is a right, but

as with every right that ever existed, it is not unlimited . . . in its exercise.

That qualifier is extremely,

even vitally important. Every human

being has all natural rights, including life, liberty, and private property, by

nature, that is, simply because he or she is a human being. That means that the right to be alive, to be

free, and to be an owner is absolute, inalienable, inherent, unlimited, so on,

so forth, etc., etc., etc., no ifs, ands,

or buts.

The general norms of the

natural law, however, say nothing about how you live your life, what you do

with your freedom, or how you use what you own, or what you may own. All of these constitute exercise of your

rights, and they are not absolute,

inalienable, inherent, or unlimited at all.

They are very much limited by your individual wants and needs, and those

of other individuals and groups, and the common good as a whole.

Thus we say that, while you

have the right to be free absolutely, your exercise of that right is

limited. In general, you may not harm

yourself, other individuals and groups, or the common good as a whole by the

exercise of your right to be free, or by any other right.

And it is this last, harm to

the common good, that so many people either misunderstand, or ignore

completely.

Take, for example, Colin Rand

Kaepernick’s refusal to stand for the

National Anthem. Our concern here is not

his reason or reasons for doing so. As

an individual, his act harmed only himself — if that. That is not the point here. Purely as an individual matter, no one has

any right to interfere with that decision.

How

about other individuals or groups? Did

Kaepernick harm anyone else by his act?

He certainly offended a number of people, but being offended, despite

all the talk of “cultural appropriation,” is hardly a criminal matter, or even

reason to do anything other than express disappointment or disagreement, even

if only raising an eyebrow. As an act

seen by others in a public forum, he was free to do as he did . . . just as others

are free to comment on it, as long as they do not, by that commentary, do harm

to Kaepernick or others.

What

about the common good?

Now

there Kaepernick may have gone over

the line. This is where his exercise of

his individual freedom may have violated the laws and characteristics of social

justice. That is what we will look at

tomorrow.

#30#