In the previous posting in this series we saw that in the

1920s, when Fulton Sheen’s thought was formed, the new concept of religion found

in the mutability of modernist and New Age thought made it particularly

attractive to, the perfect foil for, and a seemingly independent verification

of the various forms of socialism — and that socialism returned the favor. This made the pseudo science of socialism and

the quasi religion of the New Age a dangerous combination in a world that had

lost its philosophical bearings.

|

| Heinrich Pesch's solidarism was sabotaged. |

This “Manichaean mutability” accounts for the alacrity with

which the modernist movement adopted the fascist-socialist solidarism of Émile

Durkheim — as well as the later regression of Heinrich Pesch’s

Aristotelian-Thomist solidarism back to that of Durkheim by Pesch’s latter day

followers. Durkheim’s theory that

religion is a social rather than a spiritual phenomenon fitted perfectly into

the modernist demand that the Church update its teachings to conform to the

needs of the modern world, making the Church both in the world and of it.

God became a useful concept, but not strictly speaking

necessary (cf. Grotius, loc. cit.). The collected mass of the people — humanity

as a whole or the community (Der Volk)

— becomes God, or the people construct the God they need or desire. As Sheen described this development,

“In addition to the purely

metaphysical or psychological explanations of religion there is yet another

which may be called the sociological or the humanitarian. Among European thinkers this explanation

takes a double form: either that of Durkheim for whom God is ‘a divinized

society’ or that of [Wilhelm Maximilian] Wundt for whom God is the term which

represents the values of life as estimated either by the folk or the

community.” (Sheen, Religion Without God,

op. cit., 54.)

In this framework, humanity — the abstraction of the

collective, not actual human persons — takes the center. Religion becomes a way of meeting material

needs, the greatest good for the greatest number without being limited or

qualified by such things as the inalienability of natural rights of minorities

or the ungodly.

Within the new framework, spiritual needs are merged into

material needs, and the whole concept of religion must change or be changed to

conform to the demands of modern life.

As Sheen analyzed this,

|

| Fulton Sheen's thought was marginalized. |

“‘The crisis in the religious

world,’ he [Professor

Charles Abram Ellwood (1873-1946), author of The Reconstruction of Religion.

New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922 — ed.] writes, ‘has been brought about by the failure of existing religion

to adapt itself to two outstanding facts in our civilization — science and

democracy.’ [The Reconstruction of

Religion, 1922, p. 2, note in text.]

He believes that a religious revolution is in the air, and that it is

concerned with a transition from ethical monotheism to a scientific and social

conception of religion. And ‘the real

religious problem of our society is to secure the general acceptance of a

religion adapted to the requirements of continuous progress toward an ideal,

consisting of all humanity.’ [Ibid.,

p. 64, note in text.] ‘Service of God

must consist in service of man.’ [Ibid.,

p. 100, note in text.] The traditional

notion of God will then be done away with.

Professor Ellwood calls it a Santa Claus notion. ‘The autocratic conception of God, as a force

outside the universe, who rules by arbitrary will both physical nature and

human history, will be replaced by the conception of a spirit immanent in

nature and in humanity, which is gradually working out the supreme good in the

form of an ideal society consisting of all humanity. And since service of God is in reality

service of man, there will be sin in this new religion of democracy; it will be

a failure to serve mankind. In other

words it will be ‘disloyalty to society.’ [Ibid.,

pp. 139, 143, note in text.]

“‘Religion means the

consecration of individual life, at first for love and spiritual ends, but

finally for humanitarian ends.’” [Ibid.,

p. 45, note in text.] (Sheen, Religion Without God, op. cit., 56.)

|

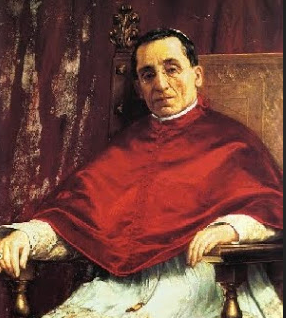

| "Forgotten" Benedict XV battled modernism. |

In the world in which Fulton Sheen developed his thought (in

common with G.K. Chesterton and Ronald Knox), the First World War had given

socialism and modernism a tremendous impetus due to the general failure to

resolve the problems caused by the “new things” — although not for the want of

effort on the part of Leo XIII, Pius X, and Benedict XV. Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany (and, not to

seem exclusive, Fascist Italy) were the natural outcome of the reaction against

capitalism and the new things combined with the devastation of the Great War.

As a result, socialism and the New Age became entrenched in

the psyche if not the economy and daily life.

No country seemed able to resist.

Both the United States and Imperial Japan, as well as many other

countries, fell victim to the new way of thinking and the abandonment of sound

philosophy.

It becomes evident why, in addition to its socialism, then, the

Nazi movement incorporated so much New Age thought in its formative period in

the 1920s. As Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke

explained in his book, The Occult Roots

of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and Their Influence on Nazi Ideology (New

York: New York University Press, 1992), this did not mean actual demonic

influence, as a number of lurid fictional and semi-fictional works

suppose. Rather, Goodrick-Clark

demonstrated that Nazi ideology (particularly its racial theories) had its

roots in esoteric theories, especially ariosophy, a school of thought heavily

influenced by theosophy.

|

| The (fictional) German judiciary on trial at Nuremberg. |

Eventually the Nazis established what amounted to a

pseudo-pagan theocracy, with socialism supporting its New Age “philosophy,” and

esoteric thought supporting National Socialism.

Nowhere was this more obvious than in the changes introduced into the

German legal system — something with which every viewer of the Stanley Kramer

film, Judgment at Nuremburg, should

be familiar. As George Holland Sabine described

this development,

“The judiciary . . . completely

lost its independence and security, while at the same time judicial discretion

was extended practically without limit. The law itself was made studiously

vague, so that all decision became essentially subjective. The penal code was amended in 1935 to permit

punishment for any act contrary to ‘sound popular feeling,’ even though it

violated no existing law. . . . Obviously no rational administration of such

statutes was possible. Equality before the law and due process were supplanted

by complete administrative discretion. What totalitarianism meant in practice

was that any person whose acts were regarded as having political significance

was quite without legal protection if the government or the party or one of

their many agencies chose to exert its power.”

(George H. Sabine, A History of

Political Theory, Third Edition. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston,

1961, 918.)

|

| Pius XI's social doctrine was ignored. |

Within the Catholic Church, “social justice” came to mean

meeting individual needs on a large scale, rather than that at which Pope Leo

XIII hinted, “the restoration of [the social order]

according to the principles of sound philosophy and to its perfection according

to the sublime precepts of the law of the Gospel.” (Quadragesimo

Anno, § 76.) By 1931, when Pope Pius

XI presented his completed social doctrine based on the act of social justice

directed to the reform of the institutions of the common good, not any

individual good, the teaching fell largely on deaf ears.

By the late 1950s when the New Age seemed to have passed and

the dangers of socialism exposed, John XXIII thought it “safe” to convene a

council. This would allow him to restart

the work of Pius IX and Leo XIII and address the new things interrupted by the

decades-long struggle against fideism — what Dr. Ralph McInerny later identified

as the greatest danger to the Catholic Church (and by extension to all religion) today.

That John XXIII’s confidence was misplaced is

self-evident. Socialism and modernism,

much less the New Age, had not been defeated, but had simply gone into hiding

after a fashion, and needed only the right opportunity to resurface. The aberrations that followed Vatican II,

however, would not have gained so much ground had not the whole nature of what

it means for something to be true changed.