The financial world is in an absolute panic, the economic

mavens are freaking out, politicians are starting to wonder if they should

start looking for honest work . . . until they remember that their financial

and economic policies have ensured that there won’t be any jobs waiting for

them. What to do, what to do? And (for us normal people) what the heck is

going on, anyway? What is causing all

the fuss?

The prices

of basic commodities are going into the cellar, that’s what. The sky, er, the price level is falling. We’re all doomed. This is a “crisis,” at least according to

those people who make their money by moving money, i.e., those whom Pope Pius XI described in the following terms:

“In the first place,

it is obvious that not only is wealth concentrated in our times but an immense

power and despotic economic dictatorship is consolidated in the hands of a few,

who often are not owners but only the trustees and managing directors of

invested funds which they administer according to their own arbitrary will and

pleasure.

“This dictatorship

is being most forcibly exercised by those who, since they hold the money and

completely control it, control credit also and rule the lending of money. Hence

they regulate the flow, so to speak, of the life-blood whereby the entire

economic system lives, and have so firmly in their grasp the soul, as it were,

of economic life that no one can breathe against their will.” (Quadragesimo Anno, §§ 105-106.)

|

| Look, guys, it's easy. Own labor AND capital! |

To a normal person, however, falling prices for basic

commodities is a good thing, whether you’re a producer or a consumer (in a

Kelsonian world, of course, you’d be both). Everybody needs the three Fs, food, fuel, and

fiber. How much they buy, however,

depends on how much their money is worth.

When prices go up, people buy less.

When prices go down, people buy more, at least until their wants and needs

are satisfied (we won’t bore you with the Theory of Marginal Utility today,

however; just assume — contrary to what economists tell you — that people can be satisfied in both their wants and

their needs).

In accordance with the laws of supply and demand, and everything

else being equal, if prices fall for basic commodities, all other prices will

fall as producers’ costs go down.

Because the money people have will buy more goods and services,

producers will make more at a lower cost to meet the increased demand. To do so, producers will expand operations or

(as the politicians put it) “create jobs.”

In this way demand increases without the government manipulating the

money supply artificially by emitting debt-backed money, and economic growth

can proceed at a reasonable rate.

|

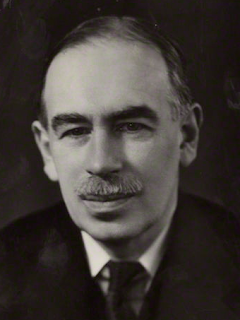

| All Hail, Our (Past) Saving Lord Keynes |

But wait! The global

economic system is predominantly Keynesian.

Our Saving Lord Keynes (as he must be known, as he proclaimed in his

Economic Gospel that it is impossible to finance expansion of operations

without first saving) insisted that you have to have inflation in order to

generate savings.

How’s that work? It’s

kind of sneaky. In order to generate

savings in the Keynesian model somebody either has to cut consumption, or

produce something useless that nevertheless has a market (nobody ever said it

had to make sense; one of these days we’re going to draw up a list of all of

Keynes’s contradictions). When the

government prints money backed by its own debt (or the money itself is the

debt) to buy stuff, this creates more money “chasing” the same goods and

services, which drives up the price level.

This forces consumers to buy less using more inflated money, and shifts

purchasing power (savings) from consumers to producers.

Translation: You got $1 per hour, but when you went to spend

it, it was only worth half an hour because the government poured twice as many

dollars into the economy without producing anything.

The Keynesian idea is thus bad even when it works —

consumers get nothing for something, and producers get something for nothing. The problem is that it doesn’t work, because

instead of hiring more workers and “creating jobs,” producers are investing in

technology that displaces workers and eliminate jobs, so people stop consuming

unless the government inflates the currency even more to finance welfare. That’s how you can have a “jobless recovery.”

So why are falling prices, contrary to the Keynesian model,

a good thing, not a bad thing?

|

| Smith: Consumption is the purpose of production. |

First, we have to understand that “reality economics” (as

opposed to Keynesian economics) is based on Adam Smith’s dictum from The Wealth of Nations that “Consumption

is the sole end and purpose of all production.”

Falling prices of basic commodities is a boon, for it allows producers

to make more at less cost, and consumers to get more for the same price.

Further, if everyone had the opportunity and means to own the

capital that is taking away their jobs, then everything would equalize. It wouldn't matter what the price was, for

production would be equal in the aggregate to income, per Say’s Law of Markets.

That is, when everyone has the opportunity and means to be

productive, then rational people only produce what they can consume for

themselves, or trade for the productions of others to consume that. In this paradigm, “money” is not something

only the government creates. In fact,

the government shouldn’t be creating money at all.

That’s because money

is simply the medium through which one person exchanges what he or she produced

for what others produced — and government doesn’t produce anything. Thus, when government starts creating money

backed by its own debt, all bets are off.

That’s because it’s consuming without producing.

But how do you get out of financing capital ownership with

past savings? By using “future savings.” Future savings represent the present value of

future increases in production. This is

in contrast to past savings, which are past decreases in consumption. Using future savings ensures that (as Leo

XIII put it) as many as possible of the people prefer to own capital. One way of doing that is through Capital Homesteading.

#30#